Delivering the business case’ was the particularly apt title of the PWI’s electrification seminar in Glasgow in April. The 140 delegates who were present know that electrification is required but convincing the Westminster Government requires electrification to be demonstrably affordable. Although various speakers described actual and potential cost reduction measures, the cost of electrification remains high at a reported £2 million per single track kilometre (stk) in Scotland and £3 million per stk in England.

This compares with £500,000 stk for German and Swiss electrification as shown in the Railway Industry Association’s Electrification Cost Challenge report. Some of these high costs are outside the control of delivery teams such as high overheads, project process issues, and the lack of a rolling electrification programme. The frustration of those who had built up experienced electrification delivery teams only to disband them at the end of each project was particularly notable.

Bill Reeve, Transport Scotland’s director of rail and Alan Ross, director of engineer and asset management for Network Rail Scotland, explained why Scotland has a rolling programme and how it is being delivered.

Scotland’s rail decarbonisation plan

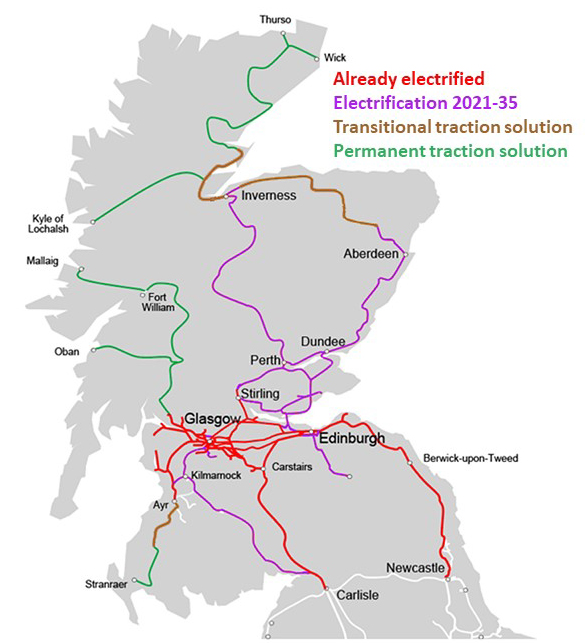

The Scottish Government considers rail electrification to be an essential part of its national transport strategy. Since 2010, it has funded 325 stk of electrification. Currently electric trains carry 76% of rail passenger traffic and haul 45% of rail freight in Scotland. Its Scottish Rail Services Decarbonisation Action Plan, launched in July 2020, will decarbonise rail passenger services by 2035.

Bill Reeve explained this plan is an instruction to the industry to electrify all Scottish main routes. He noted that battery and hydrogen trains will have a role but not for the core railway or for freight, as electric traction is essential to provide the longer, faster trains needed to meet rail freight growth targets for which gauge clearance is to the electrification programme.

Regardless of the decarbonisation imperative, Reeve explained that electrification is needed to make rail competitive as electric trains are cheaper to operate, more reliable, offer faster trains and additional services. They are also cheaper to buy than diesel trains which will need to be replaced in the not-too-distant future. For all these reasons Scotland can’t afford not to electrify.

Reeve also explained that a competitive railway is needed to attract the modal shift from cars if Scotland is to meet its decarbonisation targets which include a 20% reduction in car kilometres by 2030. Reeve noted that simply changing cars from petrol to battery powered “won’t cut it”.

Hence, Scotland is committed to a rolling electrification programme derived from a whole-system approach that considers the optimum infrastructure and rolling stock solutions to deliver the required timetable. This also gives the supply chain confidence to develop its workforce and capabilities. Reeve concluded by stressing that all this depends on cost effective electrification delivery.

Delivery

Alan Ross then explained how the decarbonisation programme is being delivered. He also stressed the need for a rolling programme to drive costs down but accepted that this requires trust and commitment. In this way, rather than individual projects, electrification is delivered as a programme which offers opportunities for optimising logistics, packaging feeder station delivery and procurement savings with early purchase of raw materials. He emphasised the need for a “sweet spot” to optimise delivery volumes which, for Scotland, is the annual delivery of around 90 stk of electrification and 30 structures clearance interventions.

Although Scottish electrification had generally been delivered within its cost envelope at around £2 million per stk, costs still need to be further reduced. This requires transparency to ensure all cost drivers are understood, the need for a culture that embraces continuous improvements and a production focus. Ross recognised that Network Rail had to respond to the supply chain’s concerns, particularly in respect of access strategies.

He also described how Scotland’s whole system approach helped to determine the best overall solution. For example, the need to withdraw diesel units in the next few years requires an interim strategy of discontinuous electrification with EMUs fitted with batteries that can be removed in future. Such an approach provides incremental benefits prior to full electrification.

Scotland’s electrification has challenges, of which its most iconic structure is one. Ross considered that Forth Bridge electrification is “challenging but doable.” There are also significant gauge clearance issues elsewhere, particularly on the Highland Main Line. He also noted that power supply in remote areas is also a challenge for both Network Rail and the National Grid.

Delivering more electrification than ever before over a 13-year period with ongoing cost savings is a significant challenge. With everyone playing their part, Ross feels this is achievable.

Stirling Alloa Dunblane (SDA)

Warren Bain, PBH Rail’s technical director, explained how the recent SDA Scottish electrification programme started in January 2016 with its first OLE Form A. It had to be completed by December 2018 so that new Hitachi class 385 EMUs could replace the class 170 DMUs that had to be released south of the border. SDA provided 110 stk of new electrification which included 2,200 new structures with an expanded feeder station and two new Track Section Cabins.

For SDA, PBH rail developed a single section pile up to eight metres in length to avoid splicing the high percentage of piles that were longer than the standard 5.5-metre length. These piles were developed in consultation with the fabricators after confirmation that piling rigs and trailers could lift and transport these piles. A particular challenge of this project was the 600-metre Kippenness tunnel, that had a low uneven roof in which OLE structures could not be installed at the low points.

Production based electrification

Rob Sherrin of Leeps Consulting has no doubt that electrification needs a production rather than a project philosophy. He quoted cost savings from repetitive programmes such as windfarms that are expected to generate electricity more cheaply than gas-fired power stations in 2023, and Network Rail’s Southern power supply upgrade which was around £800 against its £1 billion budget.

The need for such a production approach was highlighted by a questioner who asked why the GRIP language of projects is used for electrification which should be a continuous process. There was no satisfactory answer to this powerful question.

He advised that English electrification was currently costing about £3 million per stk and that this must be reduced with a relentless focus on costs and the efficiency of repetitive tasks. He considered that the overheads and prelims must be reduced as these were often many times the cost of the actual work. Also, innovation needs to focus on cost and eliminate complexity, the access regime needs to allow efficient production and multiple packages of work will provide competition.

Sherrin also felt that the authorisation regime needed to be challenged as the Common Safety Method needed to be applied on the basis that there are no new fundamental risks from railway electrification schemes.

Amey’s engineering manager, Anne Watters, reinforced many of Sherrin’s points. She explained how a 50% increase in possession time (from four to six hours) could double working time (from two to four hours) and therefore cancellation of the first and last trains of the day needed to be considered.

She also considered the practicalities of using different types of machinery. High Output trains had their advantages but needed to be able to store sufficient material for an eight-hour shift. Road Rail Vehicles (RRVs) are useful in complex areas but may not be efficient if their access points are miles apart.

Watters also stressed the importance of developing the workforce and that this related to the access regime as excessive reliance on Saturday night working increased the need for “weekend warriors.” A continuous programme also facilitates apprentice schemes, avoids efficient teams being disbanded and is needed if there are to be sufficient OLE construction trainers.

She considered that other benefits of a rolling programme were a long-term look ahead of route clearance work, enabling it to be done first, and consistency of standards. She noted that she had spent hours discussing standards for station foundation designs.

The respective M&EE professional heads of Swietelsky and Babcock, Calumn Oates and Nick Wilkinson, explained how Swietelsky Babcock Rail had developed specialist electrification plant. Its self-propelled Kirow 250 Rail Crane can be fitted with a side mounted tube driving system that can drive up to five piles per hour at a maximum 16-metre reach. They explained how their cranes can also be used to install masts and gantries. A continuous programme is needed to make the best use of this impressive, though expensive plant.

Preparing for electrification

Alan Kennedy, lead OLE engineer for SPL Powerlines, considered pre-work measures to maximise efficient delivery. He considered digital twin to be a real step change as they reduced the requirement for on-site surveys as well as improving design and constructability reviews.

Another promising development is ground penetrating radar (GPR) to reduce the need for trial holes. This enables around 25 locations to be surveyed in a shift which would otherwise dig one or two trial holes, though GPR does not completely remove the need for trial holes. Instead, it allows them to be targeted as required. Kennedy explained how GPR is being trialled on the Haymarket to Dalmeny (H2D) scheme that should have its first piles driven at the end of June.

He also described trials undertaken at a local quarry to determine the best method of rock piling and its effect on possessions. Methods tested included down-the-hole (DTH) hammers, micro-piling, and coring or auguring.

Reducing ‘boots on ballast’ and maximising time on track are key principles of efficient electrification. This can be achieved by off-track OLE construction and pre-registered cantilevers attached at site. Kennedy advised that this reduces site visits from three to one prior to wiring. However, this approach requires mature design and space for fabrication. It also needs a gap between foundation and OLE work to make it efficient.

He also explained how maximising span length at Almond viaduct on the H2D scheme might save £250,000 as the viaduct was not suitable for attachments. Although still to be confirmed, it was expected that the required 88-metre span would be feasible. Certainly, this approach has wider benefits in similar locations.

Kennedy’s presentation reinforced many of the points made in earlier presentations including the need to optimise access strategy, keep things simple, the need for a more appropriate assurance regime, and the development of the workforce.

Heritage

Another issue that needs to be considered early in any electrification scheme is its heritage implications. Michael Ponting, overhead line solutions lead for Jacobs in York explained what this entails. There are potentially many stakeholders involved with any affected stations, overbridges, and heritage assets close to the railway. Early engagement with such stakeholders is essential.

Although electrification normally requires a standardised approach to maximise efficiency, heritage impact mitigation may require a bespoke solution to be agreed with stakeholders, at an early stage of design. Ponting also emphasised the importance of challenging standards to, for example, minimise heritage impact.

Kennedy referred to the useful guidance in Network Rail Standards NR/GN/CIV/100/02 “Station Design Guidance” and NR/GN/CIV/100/05 “Heritage: Care and Development”. These show that there are over 200 listed stations in the UK, all of which require conservation management plans to be prepared in consultation with the Railway Heritage Trust.

Design

Garry Keenor, professional head for electrification at Atkins, gave a presentation focused on design cost reduction by digital design and challenging standards. He said that with typically 3,500 structures for 100 stk of electrification, design was a volume game that needed to be automated as far as possible using the latest digital design tools. He noted the importance of defining minimum viable product and emphasised that design development is the time to reduce costs, though this needs planning further ahead.

He explained that some standards may be out of date and that the historic reasons for them may not be clear. Hence there was a requirement for intelligent rule breaking to challenge standards using an evidenced based, first principles approach. He gave two examples where there had been a successful challenge: allowable uplift and wire gradients.

Until recently, the design uplift for contact wire bridge arms was 70mm. Keenor explained how novel measurement techniques that required no track access of OLE mounted equipment had demonstrated this could be reduced to 45mm.

A study of wire gradient was the result of it not being possible to demolish Steventon bridge during the GW electrification works. As this bridge was 400 metres from a level crossing, bi-mode trains had to operate on diesel power underneath it. This was because the then standards required a 60mph speed restriction of electric trains on the resultant 1 in 202 gradient and a maximum 1 in 625 gradient to operate at 125mph. After modelling and test train running undertaken by Atkins, it was demonstrated that electric trains could run at 110mph on a 1 in 175 wire gradient.

Keenor said there needed to be a cultural change to encourage intelligent challenge and interpretation of standards. He encouraged Network Rail and its contractors to follow the E&P Technical Advice Note Ref 12-21-001-V1 “Bridge parapets electrical risk assessments” which introduced a risk assessment methodology to determine the required parapet works. He emphasised the need for simplicity, both of design and process, and made the tongue in cheek observation that Britain requires more paperwork per electrification stk than any other country in the world.

Atkin’s Technical Director, Paul Hooper, considered what UK electrification might look like in 2050. Although Scotland is implementing its rail decarbonisation plan, the Westminster Government has yet to commit to an overall plan of rail decarbonisation. It has also not responded to Network Rail’s Traction Decarbonisation Network Strategy (TDNS) which recommends 11,700 stk of electrification with battery and hydrogen trains respectively operating on 400 and 900 stk of track with currently no clear technical choice for 2,300 stk.

He noted that there were various proposals for discontinuous electrification though this was not suitable for freight. This is to be a permanent solution for Transport for Wales as the South Wales Valley lines are electrified. Hooper considered that this will require an ultra-reliable system for pantograph raising and lowering. It will also need battery size to be optimised which may result in bespoke trains.

In Scotland, the plan is for interim discontinuous electrification which needs to be planned around nine new feeder stations and take account of the need to provide power for both traction and battery charging. He noted that a rolling programme needs a five-year look ahead, especially in respect of power supplies.

New technology such as intelligent infrastructure, digital twins, and static frequency converters can reduce costs. However, Hooper emphasised that the electrification programmes should not await future innovations but be planned on what we know now.

Hearts and minds

Mott MacDonald’s head of rail systems, David Wilcox also considered the traction mix recommended by TDNS and explained this in terms of how far a train can travel per kilowatt hour. It might be obvious that electrification is the optimum traction and decarbonisation solution, but it is essential to win the hearts and minds of politicians.

He considered that a whole system approach needed to be taken to maximise performance and minimise energy consumption. To illustrate this, he considered a bridge on a 1 in 200 gradient on the Borders Railway with a 60mph speed restriction on a 1 in 80 gradient. He wondered how long it would take to recoup the cost of eliminating this restriction from the resultant fuel and performance savings.

He echoed the points made by previous speakers about challenging standards, data driven design and digital twins and wondered how long it might be before drawings were not needed.

Looking to the future

Decarbonising the railway with a rolling electrification programme that provides cheaper, faster trains to attract traffic from less carbon-friendly transport is a vision for the future that is being delivered in Scotland. Hence Glasgow was a good venue for the PWI’s electrification seminar which highlighted examples of good practice in Scotland and elsewhere.

With many speakers stressing the importance of developing the workforce, the presentation by Megan Schofield on attracting young engineers to the industry was particularly well-received. Meghan started her railway career with Arup just over two years ago as a graduate OLE engineer. In her first job she worked on platform extensions at London’s Liverpool Street station. This was a small job involving all disciplines which she felt provided a good learning experience. She is now working on the Transpennine upgrade.

Schofield advised that, at university, her fellow students did not consider rail as a career and instead looked to the automotive, aerospace, and oil and gas sectors. Hence, she posed the question of what the industry can do to attract more engineers. She also felt that it was important to get more young people into engineering at an early stage.

She also felt that mentoring was important and advised managers to inspire those less experienced than themselves by spending quality time with them. She recognised the importance of networking and felt it important to have strong female leaders in engineering teams.

In the following Q&A session it was noted that Megan had clearly shown the importance of learning by doing and that mentorship was not a one-way process. One senior engineer acknowledged how much he had learnt from younger engineers.

In summing up the conference, its chair, Peter Dearman, considered that it was uplifting to hear that in Scotland, Bill Reeve, representing Government, and Alan Ross of Network Rail were talking the same language. Yet he cautioned that the UK has the highest infrastructure cost base in Europe and that, even if material cost was zero, UK electrification would still be more expensive than in Europe with much of this due to high overheads.

Regardless of the Scottish example, much still needs to be done to convince the Westminster Government of benefits of electrification and that the industry can deliver at an affordable cost.

Image credit: PWI / David Shirres