Between 24 and 26 June, seven teams of apprentices, undergraduates, and graduates gathered at the Stapleford Miniature Railway just outside Melton Mowbray for the 10th on-site Railway Challenge, sponsored by the Institution of Mechanical Engineers (IMechE) Railway Division. The event started in 2012, but was held online in 2020, due to the coronavirus pandemic.

The Stapleford Miniature Railway is a private 10 ¼ inch gauge (1/5th scale) railway, owned by the family of the 4th Lord Gretton, and operated for charitable purposes by the Friends of Stapleford Miniature Railway (FSMR). The Railway Challenge has exclusive use of the site where many of the contestants camp for the duration of the competition. The last team to arrive was the team from Poland who had suffered a puncture during transit through the Netherlands which resulted in a hospital visit for one of their number. That didn’t dim their enthusiasm, however.

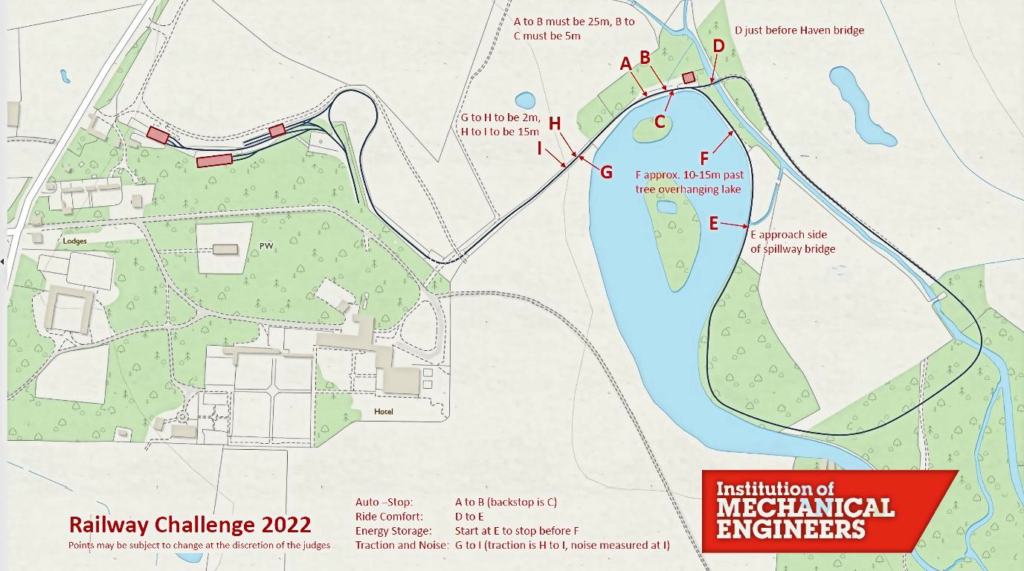

The competitors are required to build a locomotive to haul two of FSMR’s carriages (circa 1.2 tonnes) around the approximately two-mile circuit while undertaking a number of challenges. They also have paper-based and presentation challenges to complete. All the challenges relate to real life situations that contestants might encounter if working on a full-scale locomotive and, while the nature of the challenges has changed little over the years, teams still find them rather tricky.

Since 2012, the locomotive designs have changed. In the first competition, all bar one of the teams developed locomotives powered by petrol generators while the University of Birmingham developed a hydrogen fuel cell locomotive. In 2022 only one entry was powered by a petrol engine − the rest were powered by a variety of types of battery. In a previous competition, the team from Aachen in Germany also offered a hydrogen locomotive (pictured below), although this demonstrated that hydrogen powered locomotives depend on the whole hydrogen supply chain; transporting the locomotive from Germany was straightforward, transporting hydrogen was not!

A team effort

The competition depends on the cooperation of three groups. First, the FSMR team led by Richard Colby, are in charge of all activity on the site they manage, and akin to the main line safety regime, they are the duty holder. Second, the excellent team of Lucy Killington, Natalie Bradshaw, and Kirsty Joyce from the IMechE staff, who organised the facilities and equipment needed. Third and finally, the IMechE volunteers, including eight past Railway Division Chairs, and who were split into three groups − operational interface with the railway led by RSSB’s Bridget Eickhoff, scrutineering that the teams’ locomotives are safe to run led by TfL’s Tim Poole, and the judges that assess the performance of the locomotives in the various challenges led by Transport Scotland’s Bill Reeve. Many of the judges, your writer included, are not getting any younger, so it was great this year to welcome two new trainee judges − Trans Pennine Express’s Alice Callaghan (a former competitor) and Scotrail’s Blair Hutchinson.

Safety is, of course a key requirement, starting with delivery. Each team is required to provide a loading/unloading plan/risk assessment with unloading observed by an IMechE engineer. These locomotives weigh between 0.5 to 1 tonne and one would not want one to land on someone’s foot. Sometimes a little (or a lot) of reassembly is required. Unloading happens on the Thursday, unless delayed by punctures!

All the teams are required to demonstrate, in a video, their commissioning and reliability proving runs prior to arrival at Stapleford. This year only three teams – Aachen, TfL, and Sheffield submitted videos. It is no accident that two of these three teams gained the maximum reliability score during the competition as they had already proven their reliability. Unfortunately, Sheffield’s innovative two module locomotive was subject to modification after its reliability runs which led to some electrical damage − another issue that full size rail vehicle engineers face. Sadly, this issue affected the teams progress throughout the weekend.

Network Rail and Alstom’s locomotives looked more or less complete quite early on, but both Huddersfield and Poznan had some considerable reconstruction to do.

Close inspection

Friday’s first task is scrutineering. Tim Poole and his colleagues assess that the as-built design complies with the requirements. Is it in gauge? Will the locomotive stop on demand? If the emergency brake is tripped, what happens when it releases − does the service brake remain applied? Is the horn loud enough? Are there clear instructions for the driver? They also keep a handy watering can to check watertightness.

This is the first time that volunteers and judges see the various ideas the teams have incorporated. Your writer is deputy head judge and judges the design competition where the locomotive design is explained, but even with this prior knowledge it is still exciting. For your writer, the quality of Poznan’s welded bogie frames, the cleverness of Aachen’s steering bogies, and TfL’s innovative approach to delivering a graduated electrically released spring brake system were particularly noteworthy. In a later tour with Bill Reeve, we were particularly impressed by the Alstom team’s pull-out battery trays made of composite material. This contributed to their success in the refuelling challenge.

After static scrutineering, each team’s locomotive is coupled to two FSMR wagons and the train, under the control of an FSMR guard, sets off to run round the line for dynamic scrutineering which includes a brake test. Many of the locomotives use chains to drive the wheelsets and this is usually where chain alignment or tension problems are experienced.

The challenge begins

Once a locomotive has passed scrutineering, teams are given time slots to go out and practice the various challenges. Even if they have tested them on another 10 ¼ inch line, the particular, characteristics at Stapleford might alter calibration. For example, the auto-stop challenge might have been tested on straight flat track, but at Stapleford it is on a slight down gradient on a slight right hand curve. The Aachen team, who used GPS for position sensing carried out their calibration run and achieved a creditable result of 1.2 metres short of the stop point. However, after calibration, their competition result at 1.7 metres short was, sadly, worse. This is another area where engineers working on full size ATO railways take many attempts to achieve reliable accurate stops.

By Saturday, Alstom were still struggling as their locomotive’s motors seemed to be fighting each other. They eventually realised that sending speed signals to the motors was leading to instability. Sending torque commands would have been better but would not have been an easy fix so they resolved the issue by running with fewer motors connected.

While all this is going on, Poznan were still building and Sheffield were hopeful. But the Huddersfield team discovered a serious fault with their petrol generator and despite a visit to the University for spares, they were unable to rectify the situation.

The maintainability challenge starts on Friday afternoon and involves safely removing and refitting a wheelset in the shortest time. TfL, the winning team, managed to lift the locomotive, disconnect the wheelset, roll it clear, and reassemble in just under four minutes. All seven teams managed to complete this challenge, but the team that struggled most took nearly 30 minutes.

Next was the refuelling challenge in which teams had to refuel safely in the shortest time. The specification had always set a maximum refuelling time of two minutes. The organisers had thought this would be ample time for refilling a petrol tank from a jerry can (cold engine, electrics off), but recognised that recharging batteries would take much longer than two minutes even if FSMR had somehow acquired a bank of Tesla super chargers. Changing batteries is therefore accepted as a refuelling method and the winner, Alstom/University of Derby, managed to change their four lead acid batteries in just under one minute − less than half the time it took Huddersfield to refill their petrol tank from a jerry can.

The final day

On Sunday morning, only the Aachen, TfL, Network Rail, and Alstom teams were ready to run, but it was hoped that Poznan and Sheffield might be able to demonstrate their locomotives after the competition was concluded. The FSMR team run passenger trains between the competition entries, this year hauled by an Atlantic (4-4-0) steam locomotive named John H Gretton. This is followed by a competition entry (competitor’s loco and two wagons) and a petrol-powered locomotive in the pattern of a BR Warship class, known as “the diesel”.

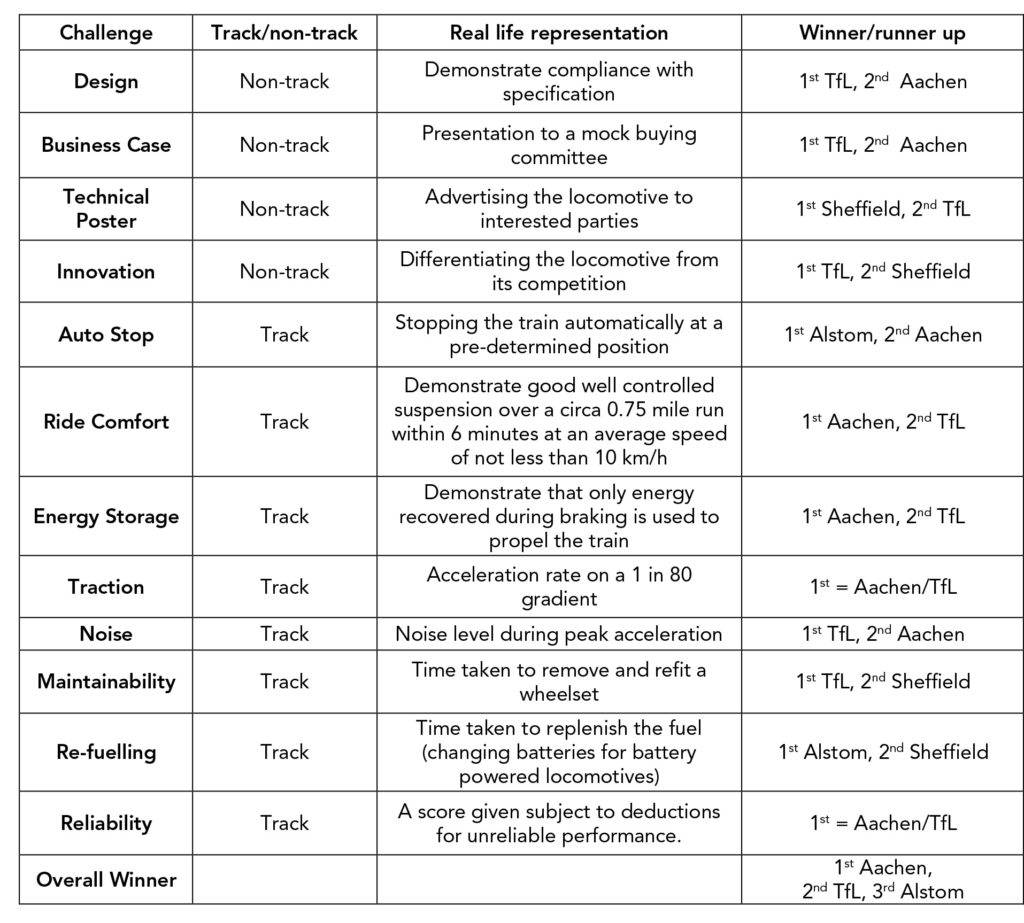

Aachen were first to carry out their tests. Their ride quality, based on EN 12299:2009 ‘Railway applications – Ride comfort for passengers – Measurement and evaluation’ (section 6.7.2 – Mean Comfort Standard Method), was a winning 3.18, and distance travelled using only the energy recovered during a service brake stop from 15 km/h was a record breaking 116 metres. The traction challenge involved timing the locomotive between two points 15 metres apart on the 1 in 80 up gradient, delivering a joint winning time of 5.94 seconds and the noise level at the end of the traction test was 91.9 dB (corrected speed).

The other teams delivered the following results:

Alstom delivered a winning auto stop result of 0.16 metres short of the stop mark, a ride quality of 8.08, a traction challenge time of 7.73 seconds and noise level of 92.5 dB. They were unable to collect any energy for the energy recovery challenge.

TfL’s auto stop sensor failed to trigger the control system, despite it working on test, and although they travelled some distance on the energy recovery challenge, they were unable to demonstrate that they had only used the energy recovered in a single brake application leading to no result being recorded, although a feature of the scoring system is that one third of the points are awarded for genuinely attempting a challenge. They delivered a ride quality of 3.32, just behind Aachen, traction time equal to Aachen’s result, and noise level slightly better at 89.5dB.

Network Rail’s auto-stop system was not working and, sadly, the locomotive unexpectedly came to the end of its battery range during the ride challenge and had to be assisted back to the station by the diesel.

Prizes awarded

That concluded the track challenges. These results are made known to the visitors and teams, but not the scores nor the results of the paper/presentation challenges. This means that after judges’ deliberations to make sure that any rule infringements are properly dealt with, the prize-giving ceremony is a genuine surprise to everyone except the judges.

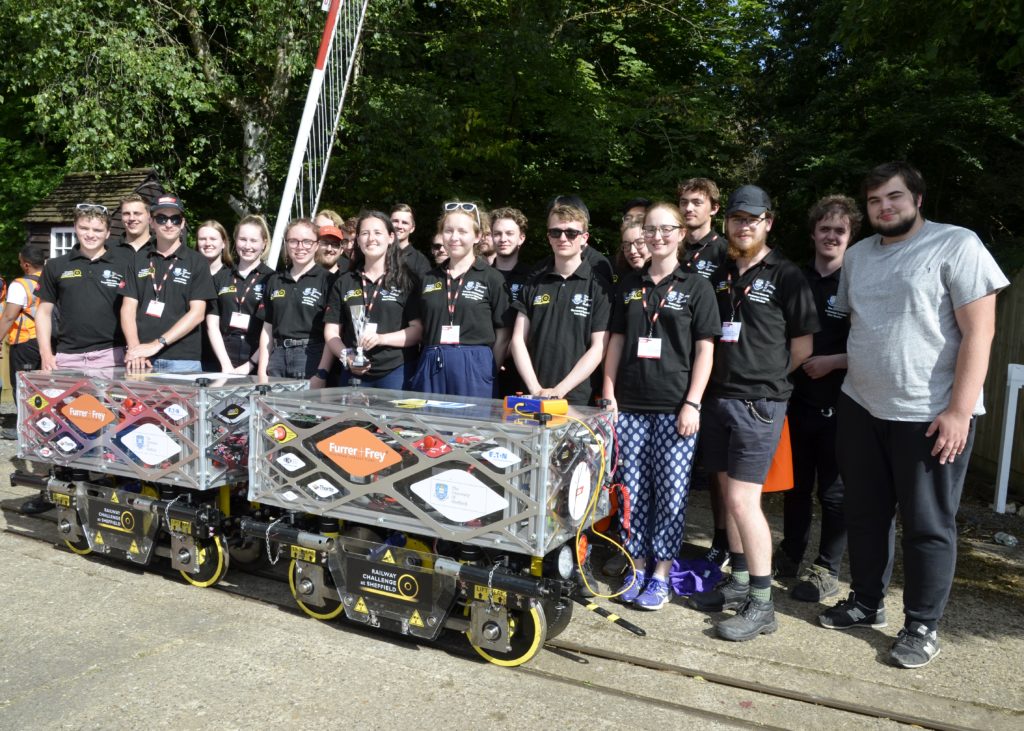

Many of the early awards (design, business case, innovation) went to TfL, but the overall winner was the team from Aachen with a score of 1660 points, 211 points clear of runner up TfL, with Alstom/University of Derby in a very close run third place. Prizes were awarded by representatives of the event’s sponsors: Network Rail, Young Rail Professionals, RSSB, and Angel Trains. The design challenge was presented by James Rollin and Lucy Marsh who also sponsor the event in memory of their father David Rollin, a founder and first managing director of Interfleet Technology (now SNC Lavalin) whose graduate trainees won the first Railway Challenge. Their sponsorship this year included donations from founder members of Interfleet collected at their 25th anniversary dinner.

After the awards, the Aachen team demonstrated their winning locomotive hauling a full nine-car passenger train around the circuit. This is some five times the mass of the specified load and is the first time this demanding, unspecified challenge has been completed without damage to the locomotive. Its performance was amazing given the small size of the lithium titanate oxide batteries demonstrated in the refuelling challenge.

Simon Iwnicki who thought up this challenge in 2010 and has chaired the organising group ever since summed up the event: “Thanks to everyone for supporting what was a truly excellent 2022 Railway Challenge. There was a real buzz all weekend and I know that all the teams got a huge amount out of it (even those who struggled most). It was fantastic to see Poznan run round successfully at the end. Overall, I think it was a really great event and I’m already looking forward to 2023! Well done everyone.”

For 2023, it is hoped that a turntable might be completed near the station which will allow more competitors than the current maximum of 12. So, dear readers, please encourage more participants to enter. Former participants and newcomers would all be very welcome.

All photographs courtesy of the IMechE, and the IMechE volunteers.