James Collinson is the 53rd Chair of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers Railway Division and has embarked on a tour of the Division’s seven Centres around the country to give his traditional address.

This year, it is likely that most, if not all, of his presentations will be given in person. His first outing at the Institution’s Westminster HQ was delivered to an audience of around 100 people with a slight majority on-line. His presentation was in three parts: Introduction, How did I get here? and So what?

Introduction

James was born in Grimsby and brought up in South Africa before returning to the UK aged 13. He took A-levels in traditional subjects for prospective engineers and studied mechanical engineering at Sheffield University from 1989 to 1992. He recalled a summer placement at Heaton depot which came about because he was required to do an industrial placement as part of the degree course and the University had a close connection with the railway. He never claimed to be a rail enthusiast, but it must have got to him as, upon graduation, he joined British Railways (BR) as a graduate engineering management trainee. He did the usual “Cook’s Tour” of the various departments including a project studying leaf fall and its impact on the wheel/rail interface, coincidentally a topic that Sheffield University is still studying to this day. Since then, he has spent roughly one third of his career in the Traction and Rolling Stock (T&RS) world and the remainder dealing with infrastructure.

This has taught him that the railway is a system – or, more basically, that T&RS is no good without the infrastructure and vice versa. The ‘railway is a system’ cliché often focuses on the assets, and the people who make it work are often forgotten. As James put it: “engineering is engineering, and the laws of physics don’t change regardless of your sector – but it’s the people that make it all work harmoniously. More importantly it’s about what people do to understand the system better to deliver more benefit”.

Dots and boxes

So how does the dots and boxes game come into this? Figuratively, he said that the aim of the game is to “join the dots and own as many boxes as possible. Joining the dots is about meeting people and learning things outside one’s usual ‘box’ of knowledge and filling in a box could happen when one really got a feel for the new knowledge; not just the theory.” An example is for an engineer to really ‘get’ the wheel rail interface from a T&RS perspective.

The next stage is to ‘get’ this from the track engineer’s point of view. He illustrated how a ‘box’ describing a very simple computational fluid dynamics model can be built up with more boxes into a complex combustion chamber model and further into an engine, where other specialisms’ boxes such as cooling, lubrication and fuel management have to be included. Each must be tuned to produce an efficient whole. It’s no good making the individual boxes the best they can be unless the whole system works together.

How did I get here?

Back to James’ career. He worked in T&RS until 2000 having navigated the challenges of rail privatisation and finding himself in Maintrain at Leeds Neville Hill depot. He gradually built up a collection of ‘filled boxes’ learning about daily examination, cleaning, level 4 maintenance, level 5 overhaul and component replacement, which covered intercity and provincial, diesel and electric trains, as well as depot plant and equipment. It was not just technical boxes but learning how to work with people, manage logistics and stores, and to win work. After 10 years of joining dots and filling boxes in T&RS, James said that he was starting to feel comfortable that he knew the people he was working with and the parameters he was working within. Or so he thought.

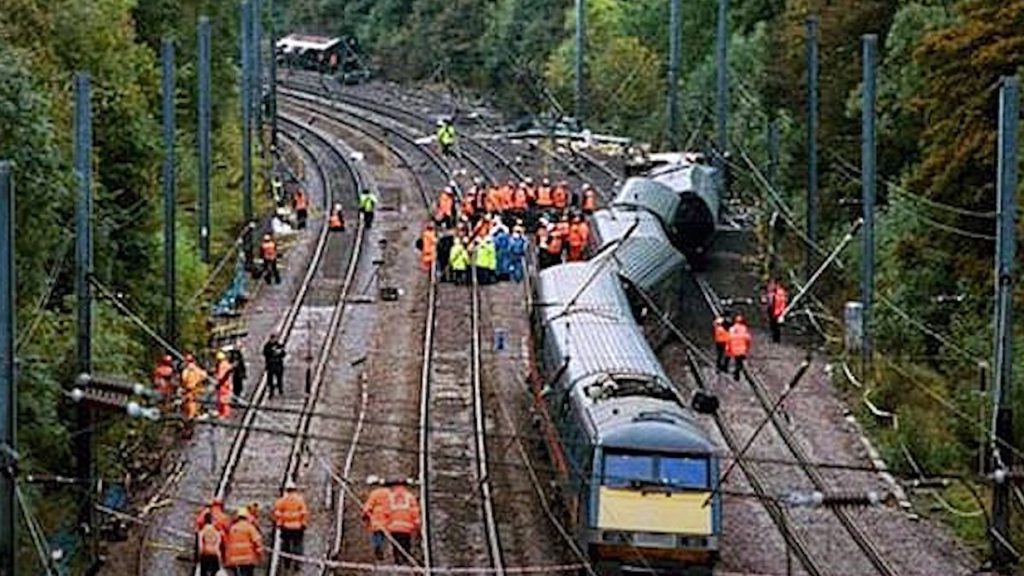

The opportunity arose to dip a toe into the track with an offer to manage an infrastructure unit covering the first 100 miles from London of the East Coast Main Line. This was something that would stretch James’ knowledge, but he thought the engineering principles would be the same, just that the assets were different and did not move – usually. This turned out to be a brave move. James was the Infrastructure Controller for his patch. “What did I know about infrastructure?”, he said, adding that he was working for Railtrack which had a reputation for being “A bit bullish” and that all the work was carried out by contractors. Unlike a depot where a good image of the location could be taken from a lighting tower, James was delighted to have a more sophisticated tool available – a helicopter. But the main task was managing the contractor – there was not a great deal of engineering involved although James did have discipline engineers for each or the disciplines (track, civil, signalling, electrification etc.,) in his team. The basic routine of carrying out defined maintenance at prescribed intervals was just like trains, but there were still dots to be joined and boxes to be filled as he learned from the asset engineers how the infrastructure worked and really saw shared interfaces from the other side. This was illustrated starkly when, three weeks into his new job, the Hatfield crash happened.

He had immediate thoughts that many of us in similar positions recognise: How did this happen? How do I deal with this? And is it too late to go back to the old job? James just got on with recovering the railway service and had a very steep learning curve, inevitably meeting a lot of new people. Some dots were joined very quickly.

Hatfield triggered fast learning about how rolling contact fatigue develops, how it can be measured and how it can be controlled. Later, when dealing with a rail wear issue, James recalled a conversation with the track engineer on his team. The track engineer asked: “When you maintain your wheels, do you work to the same ridiculous limits as we do?” Note the references to ‘your’ and ‘we’. The answer was, of course, yes; the tolerances are similar but in reverse. It was a shared experience between two professionals. Hatfield had triggered many such conversations all over the industry, sometimes for the first time in many years. James said he started to see T&RS problems from the track engineer’s perspective. “You’re out on a track walk, a long train passes, and one vehicle had loud flats,” he said. His track colleague observed that “Your trains are breaking the rails” – note ‘your’ again – and mused about the problems in identifying the right vehicle if reporting the issue. James realised that he had never thought about the impact on the track when assessing whether a flatted wheel could just do another run; he had not been thinking outside of his Neville Hill box. Of course, today there is equipment ranging from Wheel Impact Load Detection lineside equipment to axlebox accelerometers to detect wheel flats and quantify their effect on the track.

In time, James became known as the go-to guy for T&RS knowledge in his Zone as well as knowing who to talk to amongst the operators’ engineers. He became inquisitive and asked a senior Network Rail engineer “Who does this in other Zones?” This engineer replied “No one, but would you be interested?” This led to James setting up a Rail Vehicle Engineering team which was devolved and embedded into Network Rail’s Zones. This team carried out vehicles/infrastructure technical investigations with an emphasis on technical, not commercial, conversations.

In 2011, James was appointed Managing Director of the Network Certification Body (NCB), a wholly owned subsidiary of Network Rail but kept at arms-length to provide independent Notified Body, Designated Body and Safety Assessment Body certification for projects using the processes set up in the Interoperability Regulations 2011 and the EU Common Safety Method.

His role was to set up the organisation and run it at a profit whilst competing for Network Rail’s and others’ work. NCB provided services in T&RS engineering and infrastructure engineering. NCB also had to build a customer service ethic in a team whose role sometimes involved delivering bad news to customers whose projects’ assurance for conformity with standards and regulations were not good enough.

As James put it: “This was an opportunity I was looking for; the type where you don’t know what it looks like but when you see it you do a double take. You know the type – like a car or a house – you know what you’re looking for but haven’t seen one that has all you want. It’s also the type where you have a choice; ‘that’s interesting, I’ve not seen one of those before, walk on’ or ‘that was interesting, where can I get one?’ Anyway, Network Rail needed to embrace the new Regulations, they decided to create NCB and I had the pleasure of making it a reality. So many dots to join!”

The NCB role was the longest James had ever spent in one job, from 2011 to 2018. In 2018 he moved to his current job as Network Rail’s Head of Design for the South-East. Yet more knowledge boxes to fill and, after three years leading his infrastructure design team (track, civils, electrification, signalling) James still says that he is a T&RS engineer at heart.

So what?

James reflected that his career spans from the end of BR to the start of Great British Railways (GBR) and he has seen several cycles of change. He discussed what he called “A generational cycle; the end of the nationalised railway, privatisation, evolution of the privatised network, cycles of centralised/regionalised organisations (and various in between organisations too), and a return to nationalisation.”

He observed that nationalisation provides the opportunity to remove some of the barriers between private companies working to incompatible incentives; allowing engineers to bridge organisations, and allowing them to see and feel different sub-systems. He hoped that the benefits of privatisation – innovation and investment – would remain, and that any complacency arising from nationalisation could be avoided. The organisation must learn from the drivers that encouraged privatisation: competition to create innovation, investment, and customer focus.

James reiterated some key points made in presentations by Network Rail’s CEO Andrew Haines focusing on the 3S model:

Simple. A railway that is simpler and that means being more agile. A railway which is less bound by contractual obligations and long-standing, out of date customs and practices. One which is adapting to increasing shifts in demand from rail users and able to work together in true partnership between track and train, not driven by contract.

Sustainable. An affordable service that people want to use. More user-friendly, and putting the railways’ green credentials centre stage, whilst embracing technology in delivering these goals.

Separation. Being clear on roles and responsibilities, separating politics from the job of running a customer-focused railway which is relentlessly committed to delivering priorities established by ministers, and having sufficient separation to get on with the job we know we can do best.

James put it another way: “How do we encourage our new and developing engineers to join the dots and fill the boxes quickly and effectively?”

He said we need to encourage individuals to look to join the dots – literally ‘work outside the box’–- and for organisations to be ‘pushy’ in encouraging the individuals to do so.

His message to everyone was: “Make the most of the changes that lie ahead as we create GBR. For individuals, make the opportunities to learn about engineering outside of your discipline. Be brave and don’t just stick with what you know. For organisations, inspire and release your people to learn and gain experiences outside of their day jobs and invest in their development. There will be great opportunities, some might be thrust upon you; accept them and work out how to make them work. Others might just ‘walk up to you’; don’t let them pass. And finally, look out for the opportunities you can’t see; they might be just round the corner!”