Graeme Bickerdike reflects on a year which saw National Highways’ work on the railway’s great infrastructure legacy debated in the House of Lords and make national headlines before the Government brought it to a temporary halt. So, what does the future hold for the bridges and tunnels still under threat?

We have a right to know. Back in 1997, New Labour planted seeds for the Freedom of Information Act, asserting that “Openness is fundamental to the political health of a modern state” and that “At last there is a government ready to trust the people with a legal right to information”.

It’s well documented that Tony Blair soon recognised the “full enormity of the blunder”, one that was “so utterly undermining of sensible government”. But a 2011 survey carried out for the Information Commissioner’s Office revealed that most public bodies felt that the Act had increased the public’s trust in their organisation. And for those involved in campaigning – such as your writer – it’s proven to be an exceptionally powerful tool.

Hanging heads

National Highways (NH), the new name for Highways England, manages more than 3,100 disused railway bridges, viaducts, culverts and tunnels on behalf of their owner, the Department for Transport. When, in October 2020, I asked the company for a list of the structures it intended to infill or demolish as part of its asset management regime, neither it nor I could reasonably have foreseen how events would unfold, culminating in the Prime Minister supposedly putting all the works on hold after NH had enveloped a bridge at Great Musgrave, Cumbria, in several hundred tonnes of aggregate and concrete. There was nothing substantively wrong with it. The only two invested stakeholders – the Eden Valley and Stainmore railways, whose longstanding ambition to unite involved relaying track below the hand-crafted masonry arch – knew nothing about the scheme until the contractor turned up.

A queue of civil engineers condemned the shame and embarrassment inflicted on their profession. They collectively asserted that infilling is never an appropriate choice for these heritage structures, the conservation obligations for which are set out in both National Highways’ own standards and Historic England’s mandatory Protocol for the Care of the Government Historic Estate.

The opportunities presented by the green corridors spanned by these structures were being lost to a destructive policy. The ecological, environmental and community impacts received no consideration; neither did the excessive burden imposed on taxpayers. Infilling typically costs £145K, whereas a modest repair scheme might set us back £25K.

Whys and wherefores

The scale of the threat to these legacy structures was revealed in January by The HRE Group – an alliance of engineers, sustainable transport advocates and greenway developers. I became its default spokesman when the other nine members took a step backwards. Over the past ten months, £1.3 million has been spent putting nine bridges and pairs of abutments beyond use. This excludes the £7.8 million committed to the partial infilling of Queensbury Tunnel in West Yorkshire, covering 80% of the preparatory works for an abandonment scheme which has so far attracted 7,700+ objectors to its planning application.

The original list of structures threatened with infilling or demolition numbered 134, of which about half also featured on a second list of bridges that had failed their BD21 assessments to carry 40-tonne vehicles and had no weight restriction imposed. The remainder appeared to have evaded any reasonable criteria for intervention. Crucially, around one-third of the 134 structures had potential value in terms of future rail or walking/cycling schemes.

What Freedom of Information also exposed were the underhand tactics being used to drive through this programme. Infilling a bridge is an engineering activity that materially affects its external appearance; it therefore constitutes ‘development’ and should be subject to a planning application. But, as Queensbury Tunnel demonstrated, the loss of heritage assets – particularly those with a future role to play – can attract substantial opposition and most councils have adopted policies within their Local Plans which would sway the case for permission being denied.

A right to refuse

Stoke Road in the South Downs National Park (SDNP) is carried over the former Mid-Hants Railway near Winchester by a bridge dating from 1865. Today its brickwork is rather tired thanks to the ravages of unchecked ivy growth.

In April 2020, National Highways told SDNP planners that the structure is in a “distressed condition due to arch ring separation and spalled and missing masonry” and “Infilling the structure is considered necessary to prevent further deterioration and remove the risk of future collapse.” No evidence was offered to demonstrate any such threat: this hyperbole was designed to encourage the acceptance of Permitted Development rights.

But SDNP was having none of it. In response, an official pointed out that the disused trackbed was earmarked for reuse as part of the Watercress Way – an active travel route – and safeguarded against adverse development. Planning permission would therefore be required.

Nothing more was said for five months; then National Highways submitted a Permitted Development notification letter informing SDNP that the work would be carried under powers known as ‘Class Q’ which facilitate temporary works in emergency situations presenting a serious threat of death or injury.

The invoking of these powers was clearly a ruse, not least because they require the structure to be returned to its previous state within six months of work starting. Infilling, obviously, is intended to be permanent. But SDNP felt unable to contest it. Democratic process had thus been circumvented, ensuring that the transport, heritage, ecological and environmental implications of infilling would receive no scrutiny. It’s worth noting that, more than a year later, no work has taken place on site, such is the severity of the impending disaster. And NH now claims that none is planned.

Backlash

The House of Commons Transport Committee actively challenged the Government over National Highways’ infilling and demolition programme, writing letters to Baroness Vere, the Minister responsible. On 5 July, she responded to questions during a House of Lords debate. Lord Rosser accused NH of pursuing “a back-door process using permitted development powers, which stifles challenges and objections from local communities and organisations”, whilst Lord Faulkner of Worcester was more blunt, accusing the company of “cultural vandalism”.

Coverage in the mainstream press and specialist publications was universally damning, one outcome of which was the programme being put on hold whilst a formal framework and engagement process was established to determine the structures’ future. The immediate threat to dozens of structures was lifted as the least developed and most costly schemes were kicked forward into a future phase. This left about 70 on the hit-list in the short term, but an evaluation by The HRE Group suggested that at least 228 structures faced an uncertain future, with the final figure conceivably reaching several hundred. National Highways added 15 new bridges to the list in July and August.

Smoke and mirrors

An image of the infilled bridge in Cumbria – with concrete spewing from its arch – came to define the sorry saga, but its consequences for the Eden Valley and Stainmore railways did not end at Great Musgrave. Galebars No.1 bridge – built in stone and brick – carries a minor road across a cutting about three miles further south. It’s a grand lump of engineering – in need of some attention, but showing no signs of distress associated with overloading.

In October 2019, a National Highways engineer met a local councillor and the Stainmore Railway’s project manager at the bridge to inform them that it was going to be filled in, although it’s not on the company’s published list. The cost was estimated at £200K; proportionate remedial works to provide additional strength could be delivered for £40K, but the railway was told that it would have to pay for that.

NH’s 2016 Strategic Plan for management of their legacy structures made clear that “The optimal option always removes or mostly reduces all future liabilities and mitigates the risk of reputational or financial harm to [National Highways] in each case.” Thus infilling was their preference despite being five times more expensive.

“They don’t seem to understand the value of money or that of the assets they look after”, according to Mike Thompson who attended the meeting. “Whilst everyone else is trying to build a better future, they’re making it worse by damaging sustainable transport plans and blighting the environment. It’s incomprehensible and certainly not in the public interest.”

Concrete innovation

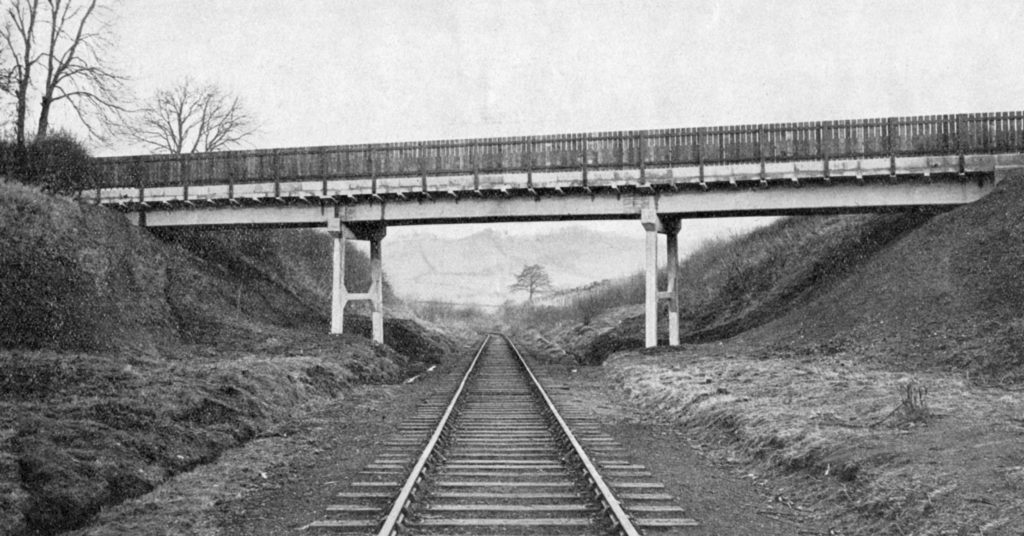

Court Pile bridge in deepest Powys is also under no threat if you believe National Highways’ list. However, contractors who’ve been on site carrying out investigations have informed locals that it’s likely to be replaced with an embankment. This structure helped to sharpen the cutting edge, being an early example of a modular precast concrete road bridge.

Back in 1935, the Great Western Railway Magazine proclaimed a “novel engineering achievement – wonderful modern methods in bridge construction”. Manufactured at the company’s concrete depot in Taunton, 155 tons of materials were brought to site and assembled by a 36-ton rail crane. Each trestle imposes a maximum load of 95 tons on its foundations which, due to poor ground conditions, comprise a cluster of eight timber piles.

Andrew Hope, who lives nearby, regards the bridge as an elegant local landmark. “It carries very little traffic and the size of vehicles using it is restricted by the narrow lane and sharp bends at both ends. It remains in good condition, with only a few minor defects. The waterlogged cutting below the structure has become an ecologically sensitive habitat.

“What the GWR achieved here 86 years ago helped with the development of sectional concrete bridges, so it’s historically significant. Statutory bodies should be working to preserve the country’s outstanding engineering heritage, not wrecking it.”

Change of direction?

Andrew alludes to perhaps the most inexplicable aspect of this tale – the blind pursuit of fractional liability reduction without a moment’s thought for the cultural loss, the environmental repercussions and the severing of a corridor that might find function again. The culture exhibited here is rooted in the 1970s, not 2021, but this is – in part – a function of the backward-looking Protocol Agreement which defines the management obligations, established with the DfT in 2015.

It’s known that there is some turmoil within National Highways as a result of the reputational damage inflicted on the company. An attempt to turn things around is underway, with a Stakeholder Review Panel formed to consider each proposed scheme before a decision is reached to progress. Only time will tell as to whether it has been bestowed with sufficient power, scope and insight to make a positive difference. Either way, infilling and demolition is expected to resume in November, with several structures earmarked for immediate attention to help consume a substantial budget underspend arising from the works hiatus.

Counterpoint

For the record, National Highways asserts that there have never been plans to infill Galebars No.1 bridge despite the minutes of their engineer’s meeting explicitly recording that intention. The company also points out that “The full extent of our plans for the next five years is published on our website” and Court Pile bridge is not on it, a truth that no-one denies. The point made by the campaigners is that a much bigger threat looms beyond the existing programme.

“The Historical Railways Estate (HRE) is an important part of our industrial heritage”, insists Richard Marshall, the responsible director at National Highways. “We continue to work closely with stakeholders to keep the estate and public safe, safeguard its future, ensure value for money for the taxpayer and re-use the assets wherever possible.

“This is why, where it is safe to, we have paused all infilling and demolition work, to give further time for local authorities and interest groups to fully consider HRE structures as part of their local plans to benefit walking, cycling and heritage railways.” But the volunteers in the Eden Valley will bemoan the pause coming too late for Great Musgrave bridge.

Many would assert that a roads company was never the right custodian for the nation’s rich railway heritage, from the perspective of either mindset or experience. Time has revealed its prevailing culture to be detrimental by default, facilitated by an inflated budget.

When Great British Railways was unveiled in May, the Government promised to end the industry’s fragmentation and “bring together the whole system”. In the House of Lords debate, Lord Young of Cookham sought confirmation that this would include National Highways’ legacy structures, a suggestion noted “with great interest” by Baroness Vere.

Those who see the value in these assets as we work towards a better normal post-Covid will be crossing their fingers for such salvation.

Lead photo: A photo of concrete spewing from the arch of Great Musrave bridge in Cumbria came to define National Highways’ bridge infilling programme. All photos credit: The HRE Group