Rail Partners, the trade body for train operators, organised the ‘Train depots for today and tomorrow’ event to bring train operators, suppliers, and other industry stakeholders together to discuss how to improve depot safety and productivity. It covered the importance of depots and the constraints within which they work, something not fully appreciated but critical to the performance of the railway. Late starts from depots, for example, affect network reliability.

Depots are safety critical environments and, although new build depots offer opportunity to get things right and improve safety, provide a better working environment, and complement the local landscape, the process of upgrading a depot can introduce safety challenges. The event also provided opportunities for sharing good practice and, looking to the future, considered plans for HS2 and how robotics can improve productivity and reduce workforce exposure to dangerous, dirty, unpleasant, or repetitive tasks, something covered in separate mini articles.

Challenges

Neil Bamford, fleet director at East Midlands Railway and formerly, West Midlands Trains (WMT), opened the event stating several challenges. Clearly, depots are there to achieve top class safety (both in terms of the depot production environment and the rolling stock itself), train performance, and train presentation. On some projects, he observed that civil engineers have, perhaps, “held sway” when building or upgrading depots and the engineer/operator voice has not been heard loud enough. He also said that Network Rail route studies did not always consider the criticality and importance of train depots and outstations with the desired output of consistently delivering excellent operational performance.

Neil worried that engineers always find a way to deliver the service in the end, but asked: “Do we compromise too much, relying on a make do and mend approach, leading to 363 days (excluding Christmas Day and Boxing Day) a year of work arounds and the consequential inefficiency and increased cost?”

He emphasised the importance of planning and management, making sure that required downtime for maintenance, servicing, and train presentation is delivered and that delays leaving depot (code MP701A, known as 701A) are correctly attributed so that the correct root causes are identified, understood, and acted upon. He added that we must move to depots that operate more efficiently and Train Servicing Agreements that are properly managed.

His final words were: “if you plan to run at 100% capacity then you’ll plan to fail; you must build in some contingency and headroom.”

Safety

Several speakers rightly highlighted safety; the prerequisite of all other activity. Neil Bamford drew attention to the fatal accident at Tyseley depot on 14 December 2019 where a driver was killed when passing between two units, just 350mm apart. The RAIB recommended improvements to hazard identification, risk assessment, and WMT’s safety assurance processes.

Dave Baston, in charge of Norwich Crown Point depot, described the safety challenges of an influx of construction workers unused to working in depots, together with another group of non-English speakers involved in the commissioning and support of their new trains and completely unaware of UK safety law and practice. As a result, he had to put in place additional management resource just to help to manage these activities safely.

Seamus Scallon, operations and safety director for First Rail, cited the Tyseley accident as part of the catalyst that led to setting up a Depot Working Group. This and three other depot fatalities in very different circumstances reinforced the need to improve depot safety. There had also been expensive damage to trains in depot derailments and, in January 2020, the Network Performance Board challenged depots to improve wrong formation and 701A performance. At that time, the depot delay incident count across the network had increased by 86% since the start of Control Period 5 (CP5).

Seamus summarised the challenges. There had been limited industry focus on depots (including yards and sidings) and there was no clear industry-wide picture of risk, safety, and performance. They were often treated as a black box i.e., what went on inside was less clear. He added that a factory type environment with moving trains was an added risk and there was limited good practice guidance. The rail industry’s health and safety strategy, Leading Health and Safety on Britain’s Railway (LHSBR), recognises that there is no clear industry-wide picture of risk and safety performance in depots and calls for improved industry-wide understanding of depot risk.

Depot Working Group

In response, train operators created the Depot Working Group, a task and finish group reporting to the Passenger Operators’ Safety Forum. Initially, it included joint working between RSSB and The Rail Delivery Group but transferred to Rail Partners although retaining the RDG and RSSB links.

With the challenges of Covid and lockdown the group rarely met face to face, but a great deal of useful work has been done. RSSB carried out a deep dive on depot safety – mostly slips trip, falls and contact categories – and identified issues such as a peak in accidents after the morning peak. The Depot Working Group has enabled improved collaboration between depots and has developed a Depot Good Practice Guidance Note (on the RDG website). There is also a Train Depot Good Practice Guidance note 07 available on request from Rail Partners.

RSSB is currently working on understanding practical depot capacities, ensuring the timetable works for depots and depot performance benchmarking. Seamus added that RSSB has delivered many activities such as economic modelling and bow tie safety/hazard modelling.

Seamus said that the task and finish group has completed its work. There is much work still to do and will now link more closely with LHSBR and there is an opportunity to widen the work to HS2 and freight. He concluded that collaboration between train depots is still needed, and Rail Partners will link depot managers together via events, workshops, and webinars.

Lessons from the past

Peter Williams, fleet and performance data manager at Avanti West Coast, took up the theme of Learning Lessons from the Past. Peter also chairs the subgroup aiming to reduce 701A delays of trains leaving depots. His theme was that depots were the ‘Cinderellas’ of the railway (according to the Collins Dictionary: “a poor, neglected or unsuccessful person or thing”).

This view came about because depots are not considered to be part of the ‘main line network’ with an inference of not being important. They tend to be treated like a black box with top management only interested in ‘what’ and not in ‘how’, and they are expected to work miracles. As Peter said: “Management thinks depots have supernatural powers to magically reset the clock at midnight, because irrespective of the carnage on the network the day before, the following day all the trains needed are expected to be offered for service on time, fully repaired, reliable, and clean”.

Peter said that depots are not adequately considered in timetable development and that not all Empty Coaching Stock (ECS) moves are even timetabled. “How can the depot plan for when trains are going to arrive?”, he asked. He added that some new trains have been ordered without any clear depot maintenance agreement and there have been examples where the trains are too long to be accommodated satisfactorily in the nominated depot(s). These two issues came as a shock to your writer with his 40+ years’ experience in London Underground, where trains are always timetabled for all moves, and where depot alterations are always part of new train procurement projects.

In the general discussion, the need for closer working between depots, TOC operations, Network Rail Operations and Network Rail timetable planners was echoed by most present, including representatives from Scotrail where the TOC/Network Rail relationship is closer than anywhere else in Great Britain.

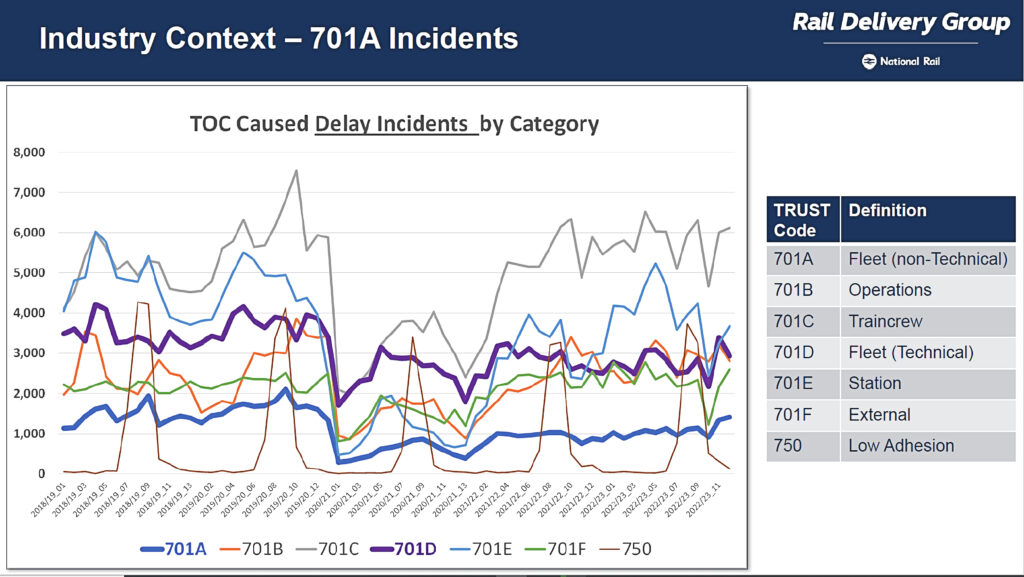

Increasing incidents

Although 701A incidents are low compared with other causes, he said, they often trigger knock on delays. The delays fell to a very low value during the Covid lockdowns and have gradually risen since, but not to the same level as in 2019. Peter’s subgroup’s tasks were to review the national data and work towards providing the necessary insight in relation to filling the gaps in the depot performance data; consider and propose how the 701A data could be used to ‘fairly’ compare depot performance; consider and propose how depot performance can be improved; reduce the number of 701A incidents; and develop good practice proposals.

One team in his group is developing a methodology to determine depot capacity. For example, a simple fan siding set might be capable of operating successfully if all sidings are occupied, but a depot might need to leave some roads vacant to allow trains to be moved around for servicing, fuelling, maintenance etc., and if those roads are filled, the depot will not be able to operate.

Some depots have defined Depot Rules (not unlike rules of the route/plan) that outline what each depot can: accommodate (frequency of incoming trains); store (capacity); maintain (maintenance activities/requirements); and deliver (times/ frequency of departing trains). These rules will be used to confirm that new or changed timetables are compatible with these requirements.

Peter asked attendees to help raise the priority of depot needs in relation to decision making, develop and enforce Depot Rules, review delay attribution processes, and make sure that incidents allocated to a depot are really within its gift to resolve.

Safety during change

Dave Baston talked about Safety during Change drawing on his experience managing Norwich Crown Point depot which formerly looked after the London-Norwich loco hauled Mk3 carriage push pull sets and a motley collection of diesel multiple units.

When the current Greater Anglia contract started, it was announced that all of these (and the Stansted Express) were to be replaced by 20, 12-car Stadler EMUs, 24 4-car and 14 3-car diesel electric bi-mode regional units, all from Stadler. They represented a significant change in technology and, for passengers, probably the single biggest innovations were train floors which were more or less level with the platforms and automatic sliding steps to bridge the gap between train and platform.

Dave explained the pain involved with such a massive change, the more so because Crown Point was not originally planned to be the depot for these trains as the proposed site in Manningree proved to be unsuitable.

He summarised the depot team’s journey in three stages:

- Pre-October 2016 – Evolution.

- One team, stable facilities, availability matched to service, high performance, stable franchise environment.

- 2016-2022 – Revolution.

- Split teams (some existing staff transfer to Stadler under TUPE), major depot change, major fleet change, low performance.

- Present – Evolution.

- Common goals, stable fleet, stable facilities, marginal gains, one team.

Interfacing issues

Dave highlighted several issues with interfacing the new trains with the depot, not least was the sheer length of the 12-car trains at nearly 237 metres, needing very careful set out of all the depot touch points – toilet and sand servicing points, for example – as well as the compatibility of wash plant brushes with a new train where the bodysides are lower than on the trains they replace. In addition, the first new depot facilities needed to be available before the new trains first ran and grew as the operational fleet grew.

Dave said that they were often “struggling to keep up” and “a high level of maths and planning was required”. But, in the end, there was a big gap between theory and practice. They found that servicing a 12-car train was a lot harder, and they sought and used alternative sites (Derby Etches Park, Ilford, and Bounds Green) to reduce the maintenance load for the legacy fleets when 70% of the maintenance sheds were lost to construction.

Dave described several of the bigger changes. On the older trains most of the maintenance was carried out from underneath, and vehicles were lifted on jacks for bogie changes. On the new trains, roof access was required for equipment displaced from underfloor locations because of the lower floors, side access to exchange diesel generators, and a bogie drop to facilitate bogie exchange on articulated vehicles that are not easy to split. Also, and inevitably, the shore supplies were different.

Managing all this safely proved to be a major task as the construction work fell under the CDM regulations and physical, interface, and management responsibilities between site management and the construction contractor, had to be defined.

There were many visitors to site including the new maintainer and commissioning teams (TSA and MSA), the transferred staff now working to the new maintainer’s rules, many construction contractor workers (in excess of 150 not familiar with depots and the OHLE environment). As Dave put it, “Piccadilly Circus moved to Crown Point”, but he noted that his responsibility as depot facility operator remained and there was a high risk to safety and operations. His advice for managing visitors included:

- Put in dedicated contractor controllers.

- Have a dedicated and separate safety team to take ownership of and investigate any accidents, incidents and near misses.

- Robustly audit and demand feedback.

- Check and approve work package plans, safety packs and lift plans.

- Make time to be out on the shop floor; don’t rely on the mountain of paper.

- Communication/briefing and toolbox talks to staff are vital.

- Have a robust induction programme (many visitors from outside the industry mean you need to act swiftly before any accidents occur).

- Have the confidence to remove/ban from site people who don’t behave safely.

Dave’s conclusion was that anyone managing a large fleet cascade will have to cope with big plans constantly changing; solutions that seem to have unacceptable compromises (e.g., bean counters say ‘no’); trying to run business as usual in the middle of a huge building site; all whilst introducing new stock and retiring and/or cascading legacy stock. There will be a backdrop of conflicting requirements hour by hour, and uncertainty for many people such as TUPE, role changes, and possibly voluntary severance. And safety is only maintained by sticking to core principles.

Enabling change

Finally in this section, Mark Knowles, leading on train maintenance/depot/stabling strategy for the Great British Railways Transition Team, outlined the emerging strategy for the sector. The current proposal assumes ‘targeted’ electrification roll out and decarbonisation objectives. The strategy is aimed at meeting the maintenance needs of a very rapidly developing mix and deployment of fleet traction types: electric, battery, diesel, bi mode, and hydrogen.

‘Principal depots’ will be a centre of excellence for rolling stock traction type.

Existing commercial agreements would be re cast to align objectives/interests.

There will be a template commercial model for new and cascaded stock to align interests.

Stabling locations will be selectively developed to improve capability.

The operator’s role as ‘maintenance controller’ will be enhanced with improved data, analysis, and knowledge.

Operational excellence model will be developed and deployed throughout.

Mark said that deployment of this strategy will create better control for the operator, improve standards, create required flexibility, provide for growth, reduce operational costs, and equip maintenance operations for the future.

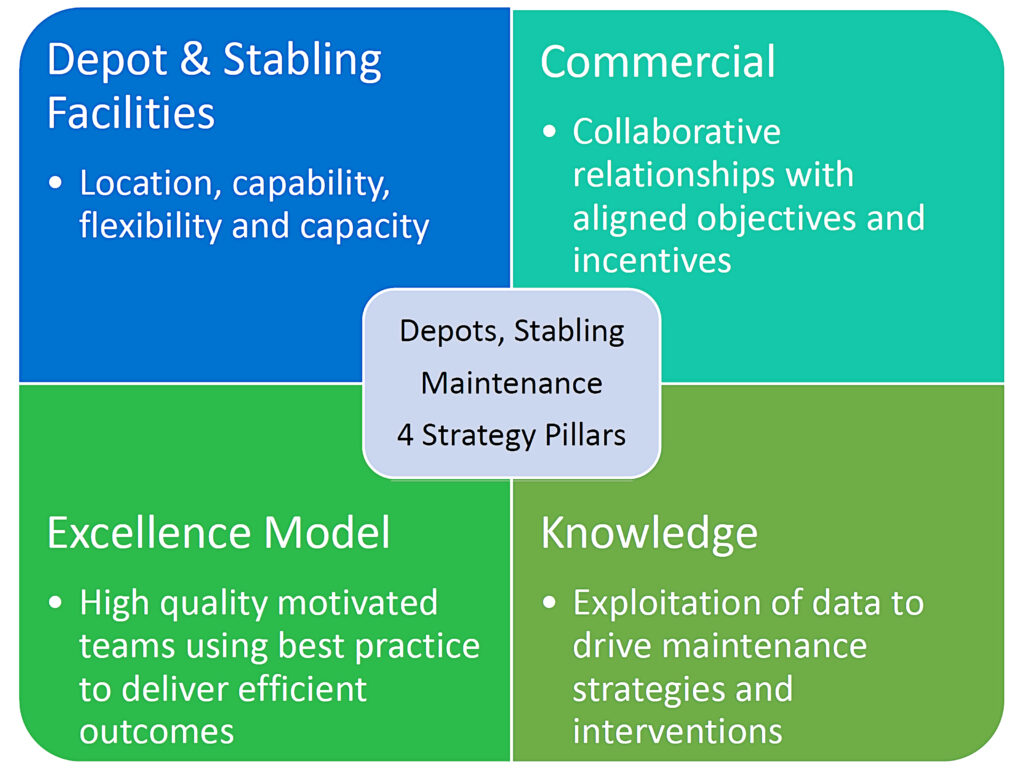

He identified four ‘pillars’ that would be used to enable change:

Pillar 1 is intended to help locate depots in the right place. Mark highlighted a depot and stabling facilities case study and said that once the train plan/timetable is determined, the purpose of Pillar 1 is to define the future roles for depots and align capacity and capability for forecast needs (including growth) driven by electrification and decarbonisation objectives and traction solutions. This strategy also proposes an enhanced role for stabling locations reducing demand for further depot development, improving service delivery, and reducing ECS costs.

The purpose of Pillar 2 is to create more permissive agreements between asset owners, maintainers, and train operators which align objectives and create the environment for flexibility, innovation, and change which will be required in the future railway.

The purpose of Pillar 3 is to make full use of available data regarding train performance and faults to inform intelligent planning, deliver timely interventions, and avoid over maintaining rolling stock fleets in order to optimise reliability at lower cost.

Finally, the purpose of Pillar 4 is to make rolling stock maintenance and service delivery a fully planned, resourced, and expertly delivered activity using best practice.

Mark concluded with expected benefits including efficient, cost-effective maintenance delivery; stable, highly trained and capable maintenance teams; lower industry costs per vehicle mile; fewer empty stock movements; greater flexibility/agility to deal with changes resulting from decarbonisation and electrification; and reduced need for depot development/extension in response to increased demand. His final remark was that there would be opportunities for private the sector.

Roundup

This seminar and a subsequent new and cascaded fleet event were intended to provide lessons learned for others’ benefit and to publicise good practice guidance now available. A takeaway was that the message had certainly landed with the Great British Railways Transition Team which is working hard to deliver a strategy that will avoid the challenges caused to depots by the recent major programme of new and cascaded vehicles.

Image credit: Adobe / Greater Anglia / Rail Delivery Group / Rail Partners /