Travelling by train can, at times, be challenging for anyone, but rail travel for customers with specific needs can be very daunting at any time. Railway stations were largely designed in the Victorian era with little thought for the needs of restricted mobility and impaired travellers. We are also fast becoming an ageing society and, by 2041, one in four of the population are set to be over 65, with increasing issues relating to physical and cognitive impairments, and restricted mobility.

The effects of an ageing population, combined with growing numbers of economically active elderly people, and people with restricted mobility, means that there is a need for rail stations to be designed and adapted for inclusivity. This creates both challenges and opportunities for operators and station designers.

Legislation

Part III of the Disability Discrimination Act 1995 (DDA), now absorbed into The Equalities Act 2010, gave disabled people a right of access to goods, facilities, services, and premises. It is unlawful to treat disabled people less favourably than anyone else for a reason related to their disability, and the rail industry is required by law to take reasonable steps to change anything which makes it impossible or unreasonably difficult for those with restricted mobility to use a service, such as using a railway station. Means must be provided that make it easier for restricted mobility people to use a service, and the industry is required to alter the physical features of premises (if reasonable to do so) if the service continues to be impossible or unreasonably difficult for people with restricted mobility to use.

It’s not just restricted mobility travellers who will benefit from good railway station accessibility. Those who are travelling with small children or are carrying luggage or heavy shopping will all benefit from an accessible station, as will people with temporary mobility problems (such as a leg in plaster). The increasing use of rail for leisure purposes also means that many customers are now carrying heavier and very often wheeled luggage. The term Persons with Reduced Mobility (PRM) covers all forms of restricted mobility, either permanent or temporary.

The best options to improve station access are not always the most expensive nor the most disruptive. Access audits can assist in providing detailed analysis of potential and actual problems and can be made based on plans for new buildings as well as by surveying existing ones. Any access audit must take account of the full requirements of PRM, including those with sensory and cognitive impairments. Audits should be carried out by competent people and improvements to access in existing buildings can often be made most economically when carried out as part of regular repair, maintenance, refurbishment, and redecoration intervention. The key is to consult and plan, both early and properly.

Guidance

There is a lot of guidance available on how to improve station accessibility and some examples of accessibility improvements include:

- Providing lifts that are automatic, well lit, reliable, easy to use, of good size, and provide an audible tone when the doors open and close.

- Staircases and platform edges with tactile warning surfaces.

- Ramps with the right slope angles and that are slip-resistant, and footbridges with handrails at the right height.

- Open entrances and ticket gates of good size, and accessible waiting rooms and toilets.

The main source of data for existing station improvements is the Department for Transport’s Code, Design Standards for Accessible Railway Stations, and station operators are required to comply with this as part of their licence when carrying out works.

There is a railway standard for platform heights, but the actual height of platforms across the rail network is varied because when the network was constructed different railway companies used different platform heights. Low platforms present entry and exit problems to everyone, particularly for mobility-impaired train users.

The relevant standard specifies that new platforms should be 915mm above rail height, have an offset of 730mm (horizontal distance between rail and platform edge) and should not be on a curve of less than 1,000m radius. Of the 6,000 platforms on the mainline network, platform height and offset requirements are only achieved for 30% and 22% respectively, with only 7% meeting both requirements. A fifth of all platforms fail to meet the curvature requirement.

This standard is a trade-off between the requirements of passengers and ensuring that platforms aren’t struck by any of the different types of trains. The loading gauge requires greater offsets at higher platform heights. Hence a 1,115mm-high platform, the typical height of most train floors, would require a 900mm offset. This compares with the 730mm offset of platforms at the standard 915mm height which research has shown to be the optimum platform height.

Ideally, there should be level boarding between the platform and the train. This is provided on Greater Anglia and Merseyrail services following the introduction of a new train fleet together with a programme to bring platforms to the required standard. Their trains have a 950mm floor height and an extending bridging piece as the door opens to permit unassisted access for those in wheelchairs.

Raising the level of a complete platform is relatively costly and not easy, although recent advances in design of an overlay system may be suitable and provide a cost and time-efficient solution. A solution developed circa 20 years ago, based on work carried out in the Hope Valley in the late 1990s, is the Harrington Hump (Easier Access Area). This is a modular and easy-to-install system to increase the height of a short length of railway platform at a relatively low cost. The system takes its name from Harrington railway station in Cumbria which was the location of the first production version in 2008. Since its installation, Harrington Humps have been installed at other railway stations across the network.

Most people are right-handed. This means it is good practice on wide stairways to sign people to walk on the right-hand side so that more people can use the handrail more easily. Your author is part disabled on his left side, but is right-handed; so does not find it easy to use the stairs at his local station as the signage does not follow good practice, requiring customers to walk on the left-hand side of the stairs.

Access audits

Whenever work of this kind is to be undertaken, access should be reviewed to see how it can be improved. Auditing access issues should also be part of the process of developing guidance, strategies, and implementation programmes. Where the area concerned is a historic environment, then the changes needed to improve accessibility should be made with sensitivity for the site environment. Early consultation with those responsible for managing a historic environment should ensure that any changes do not detract from the appearance of the area.

The term PRM is a broad one. It includes people with physical, sensory, or mental impairment, and a conservative estimate is that between 12% and 13% of the population has some degree of impairment. It is essential that any design for people with mobility impairments should be to the highest possible standards. This requires knowledge of the capabilities of different types of people.

There are many aspects of design of pedestrian environments that are helpful to all or most restricted mobility people (and many other rail customers). There are also some specific facilities needed by people with a particular kind of impairment. For example, manual wheelchair users need sufficient space to be able to propel the chair without banging their elbows or knuckles on door frames or other obstacles.

When designing or modifying facilities the aim should be to be generous in the allocation of space. Someone who walks with sticks or crutches also needs more space. It’s the same for a long cane user or a person carrying luggage, a lot of shopping bags, or with small children. So, providing adequate clear space is of benefit to many customers. Designing for PRM requires obstacle free routes across and through stations and the type and dimensions can be found in the DfT Code and the National Technical Specification Notices for PRM.

Similarly, visually impaired people need a good level of lighting and if information such as a timetable is displayed, the print size should be so that they can be read easily. Almost everyone benefits from good lighting, as it gives a greater sense of security, and practically everyone finds reading timetables easier if the print is clear and large.

More specific needs, however, can be just as important for people with certain types of impairment. An example outside of rail is the rotating cone below the push button box on a controlled pedestrian crossing. This is essential if a deafblind person is to know when the steady green man signal is lit.

Sign language

Customers with impairment issues can also be assisted by the appropriate use of technology, such as good clear intelligible Public Address (PA) systems for people with sighting impairment and good visual Customer Information Systems (CIS) for people with hearing impairment. However, there is more to inclusive accessibility than providing normal PA and CIS.

Last year Network Rail’s managed stations were provided with touchscreens showing British Sign Language (BSL) travel announcements. This followed Euston station being the first to pilot the technology in 2021. The touchscreens were developed with LB Foster based in Nottingham, and sign language interpreters created a library of standard messaging as part of the screen software system. There is also a team of interpreters on standby to make bespoke signed information as situations evolve or during periods of unexpected disruption. Messaging can be turned into BSL and the videos uploaded directly to the screens using 4G.

Some may assume that if someone is deaf then they can read, so why can’t a person with poor hearing just use the CIS? Many rail users with noise cancelling headphones never listen for train notices, and just read the CIS displays. Train stations can be hectic and train schedules can change, so surely it is quicker to read the displays. If BSL does help deaf people then would it be better to invest money in teaching station staff sign language so they can help with specific queries?

The answer is BSL is its own language with its own vocabulary and grammar. It is not ‘English with your hands’. BSL is in a different order to spoken English, so for deaf people who rely fully on BSL reading something is not easy, hence they need an interpreter to translate for them. Research also indicates that deaf people’s reading age can be behind that of hearing people. For many deaf people, BSL is their native language, while written English is a second language. If someone can speak English then learning to read English is just learning the system that encodes the spoken language. But if a deaf person can only speak BSL, then learning to read English means they have to learn English at the same time as learning to read. This is why deaf people may struggle to read.

Teaching station staff BSL isn’t that simple either. It takes at least a year of BSL Level 1 courses to learn the most basic of BSL, and at least seven years to become a fully qualified and registered interpreter. It also requires a lot of time and money to learn BSL.

The deaf community has been campaigning for many years for something like the remote BSL translation displays, so it’s a welcome initiative by the industry and a good use of technology. Let’s hope other train operators take note.

Funding

As you might expect, making stations designed in the last century compliant with modern accessibility requirements is not straight forward or cheap, but it is absolutely the right thing to do and is an investment for the benefit of everyone. In 2005 the Government set aside funding to address compliance with the then DDA service provision. Out of this came the ‘Access for All’ programme, which aimed to maximise the service benefit by providing infrastructure changes in the form of an accessible ‘step free’ route from the station entrance to all platforms served by trains.

After much detailed consultation the scheme was formerly launched by the DfT in February 2006 and has enabled around 200 stations to become ‘step-free’ and provided many other smaller-scale improvements to more than 1500 other stations.

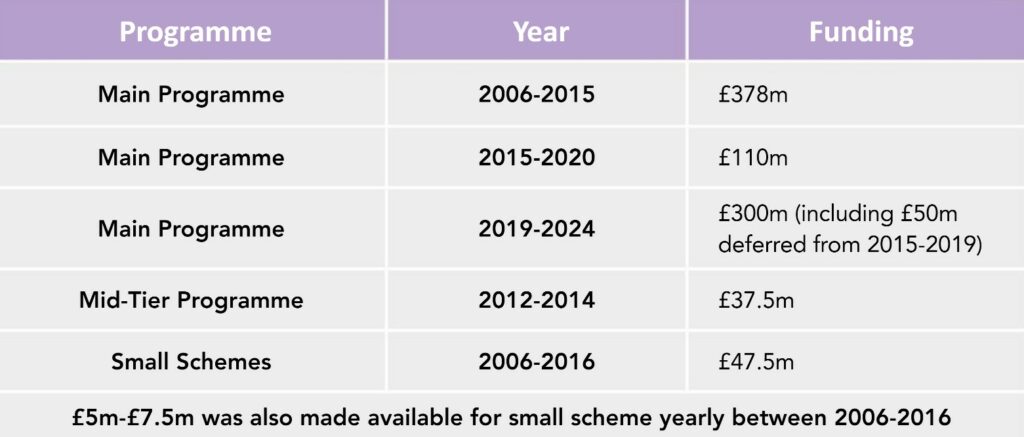

To date the funding for Access for All from Government has been:

Future funding for Access for All is not clear and it is unlikely that investment will be enough to ensure a fully accessible railway by 2030. Research by the Leonard Cheshire charity shows that to achieve this will require a significant increase to the current levels of funding.

Follow the QR code for more information.

The report recommends:

- Governments across the UK, Wales, and Scotland must put in place a legally binding duty for all train journeys in Britain to be fully accessible by 2030, backed by a sufficient funding and implementation plan.

- Renew the Public Sector Equality Duty with a focus on affirming the rights of disabled people to live independently. Principles of inclusive transport must be firmly established across Government and Train Operating Company standard practice, going beyond ‘accessibility’ considerations to a whole system approach. This includes embedding better inclusive training of station staff and tackling negative attitudes from the wider public.

- Design public transport services and their delivery based on the experiences of the people that they are intended to serve. Comprehensive and continuous civic engagement with disabled people must be incorporated from the earliest stage when taking forward the findings of the Williams Rail Review.

- The UK Government must improve its data practices to better understand – and respond to – current barriers to using the transport network. The research and analysis provided in the Leonard Cheshire report presents the economic benefits of making the rail network fully accessible.

- Disabled people should be able to expect the same standards of treatment as everyone else on their journeys. Leonard Cheshire says that accessing the right to use public transport services can be a fraught process and that improving awareness of the rights of disabled people, and how the rights are enforced is needed.

Benefits of good accessibility

The rail network fosters social inclusion by connecting people to homes, jobs, schools, colleges, hospitals, shops, leisure facilities, families, and friends. An inclusive railway ensures that everyone can make those connections and play an active role in their community and contribute to their local economy. Good accessibility should be a right and not thought of as a favour.

Station design should include the needs of everyone, to deliver social benefits and commercial opportunities. When stations are more accessible and more people’s needs are met, then the rail industry will attract a broader range of customers including people with a range of impairments, and customers with luggage, wheelchairs and pushchairs.

When stations meet customers’ needs more effectively, they are less likely to choose other transport modes. When customers have a positive user experience this helps to establish loyalty and a good reputation for the rail industry.

The author thanks Gary Tordoff of Tordoff Rail and Accessibility Consulting for his assistance with this article.

Image credit: iStockphoto.com