It is traditional that the Institution of Mechanical Engineers (IMechE) Railway Division Chair tours the country giving the traditional address, and this year’s Chair, Andrew Skinner, started in what he called home territory, Swindon, on 18 September. Andrew is the Railway Division’s 55th Chair and the title of his address, ‘Along the Way’, led to a discussion about railway engineering careers and Andrew’s view of the future.

Following tradition, Andrew summarised his career. It is always fascinating to hear about the different routes railway engineers have taken to senior positions. Andrew’s earliest recollections about railways were in the late 1960s as a small boy at a miniature railway in Clacton. It must have influenced him because, as a teenager, he helped a railway memorabilia enthusiast in his small Gloucestershire town by constructing the interlocking for a 15-lever signal frame based on a signal layout this collector had drawn.

This lever frame was unusual. The Midland railway pursued its own ideas right from the very start of signalling initially with a tumbler locking frame introduced around 1870. In a complete departure from other manufacturer’s practice, the entire locking frame was built above operating floor level, with the lever catches and interlocking mechanism all encased in a black metal surrounding. This feature had several benefits, apart from cleanliness, in that it allowed maintenance to be carried out in good light and also permitted low or ground level cabins to be built without complication. A side benefit, given that the lever pivoted above the signalman’s foot level, was that the levers were easier to swing.

Training

Andrew did briefly consider careers in the police and teaching (maths) before deciding on railway engineering and Dowty nearly poached him, its offer arriving a week before British Rail’s. But the draw of the railway was too much, and Andrew started on BR’s Engineering Management scheme in 1984, embarking on a thin sandwich course at Brunel University.

The great thing about a sandwich course is that there is a chance to see, touch, and work on real engineering whilst studying. Andrew had the opportunity to work on a huge variety of assets including the five-speed gearbox of the last Class 03 shunter to be overhauled, Class 58 build, underframe cleaning, changing brake blocks, and strip/rebuild of English Electric engines. He assisted with basic car body construction and even designed the air conditioning system for one of the Mk 3 carriages on the Royal Train.

On completion of training, he was offered the opportunity to work in the plant section but really wanted to work in traction and rolling stock. Andrew said it was time to speak his mind and, as a result, his first assignment was to Wembley depot which was maintaining Mk 2 and Mk 3 carriages for the West Coast Main Line (WCML). At the time, the Mk 3 Driving Van Trailers were being delivered and Andrew discovered two things: it was a novelty to be able to drive the train from a laptop, and it is important that inter-car jumpers are the correct length taking account of all reverse curves, discovered when their first test train blocked all four tracks on the WCML with jumpers that were too short.

Andrew’s takeaway from these early experiences was to “get involved in as much as you can and learn as much as you can however irrelevant it might seem at the time”.

Freight

Next, Andrew became senior technical officer at Cardiff Canton depot. This involved a variety of activities from locomotive naming ceremonies, clearing ancient scrap wagons from yards around Cardiff, and taking locos to Shrewsbury to test modifications to the radio system for the Radio Electronic Token Block (RETB) signalling system on the Cambrian line.

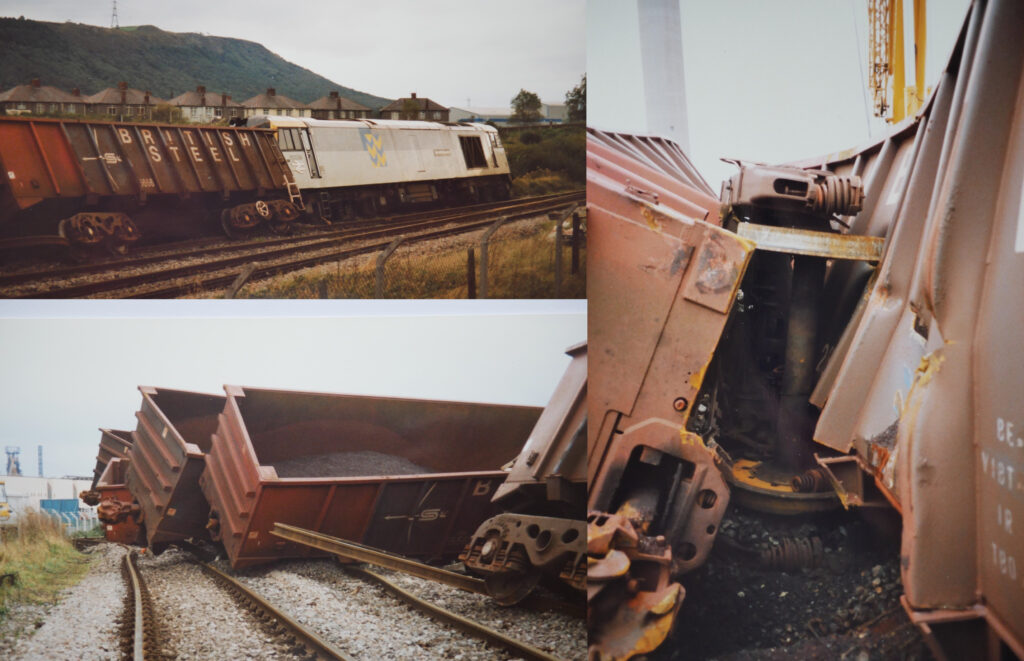

With the advent of Trainload Freight – one of the BR divisions set up as a profit centre prior to privatisation and something of a success story – Andrew was promoted to area engineer, based in Margam. There he was responsible for locomotives and also wagons which, at the time, his boss described as: “boxes on wheels, but the complex ones had bogies”. He rapidly learned the importance of processes, understanding, and compliance, and he introduced the first railway British Standard Quality System in the UK for traction and wagon maintenance and train examination.

Above all, Andrew learned how important the railway was to the then-industrialised area of South Wales. Key freight flows included coal for export and to steel works, limestone to steel works, iron and steel products from the factory, oil products from Milford Haven and munitions to the Royal Naval Armaments Depot at Trecwn.

Incidentally, at the time a 2-foot 6-inch (762 mm) gauge line traversed the entire Trecwn site, with direct access to 58 cavern storage chambers. All rail infrastructure was built in copper to reduce the risk of sparks. Serviced via its own on-site locomotive shed and works, the line was equipped with a series of specially provided wooden enclosed wagons, with sliding roof covers. This allowed sea mines and other munitions to be directly placed within the wagons from overhead gantries and transported over the entire site without access by any form of side door, hence enhancing safety.

Sort it out

From 1994 to 1996, Andrew became depot engineer at Bescot. On appointment, he was told: “you need to sort it out!” Apparently, the staff were doing a lot less work than they were paid for. They were paid for 12-hour shifts, rostered for eight, and worked four. The depot was responsible for 56 locos, had 35 staff, and an annual budget of £1.4 million (in 1994 prices). Andrew’s approach was to work with the staff as, he said: “it’s difficult to ask people to work in filthy dirty and unloved premises”. There was much cleaning, decoration, and reorganising of rosters so that, for example, locos were prepared for weekend engineering work at more appropriate times.

Andrew also put effort into getting recognition for the depot as the photo of the Bescot headboard shows. Another learning experience was when control phoned and said: “The police are on the way. When they arrive, do as they say”. The police said to him: “Jump in your car and follow us, and if we jump a red traffic light, keep following!” They were on their way to deal with a hot axlebox on a train carrying nuclear fuel! Another lesson learned was third rail and snow ploughs don’t mix – a near miss thanks to Andrew’s assertiveness.

In 1996-1997 with privatisation, Andrew was depot engineer for English, Welsh, and Scottish Railways (EWS) at Cardiff Canton. His task was to transform a large depot from locomotive maintenance to rolling stock overhaul, including training, tooling, equipment, process planning, and health and safety. Many skills were brought together with lots of new tasks – a real change of direction for many people. Moving away from locomotive overhaul, the work then included bogie steel wagons and travelling post office vehicles – from cylinder heads to laying lino.

Following a sideways move to become area engineer south (Barton Hill, Eastleigh & Didcot) in 1997-1998, and as infrastructure services manager from 1998-2000, Andrew had the opportunity to gain commercial experience. He was account manager for EWS, providing infrastructure trains to Railtrack whilst managing rolling stock resources and developing train plans. This involved an eye for detail and learning how to path trains when there were many possessions. The railway was newly privatised, and Andrew had had little direct commercial experience. He got through it by working with the customer’s team in their offices with a detailed understanding of EWS’s resources – traincrew, locos, and wagons.

Passenger

In 2000, the passenger railway beckoned and Andrew joined GWR as fleet improvement project manager, managing a smorgasbord of 30 different projects for the High Speed Train fleet, all at different stages and involving people, technical, education, and commercial skills. In 2006, Andrew became fleet engineering manager, a new role which involved forming a team responsible for fleet standards and technical engineering. Andrew and his team brought electronic systems overhaul in house, cutting costs and reducing the lead times for material repair. In addition, they started selling these services to other operators. His team also integrated new fleets such as those from absorbed operators – Thames Trains and Wessex Trains.

In 2007, Andrew became fleet manager (High Speed Services), directing and leading the four HST maintenance depots in Penzance, Plymouth, Swansea, and London. He was responsible for the safety of the fleet as well as 565 staff, managing people issues and health & safety, as well as a budget of over £35 million (excluding fuel, materials, and leasing costs).

Since 2010, Andrew has been GWR’s head of engineering, responsible for providing direction on engineering policy, standards, and assurance as well as occupational health & safety, material procurement & logistics, data analysis and reporting, and IT systems. His work has included signing into use GWR’s IET fleet as well as managing new EMUs and a BEMU. There have been many challenges to be resolved based on experience and judgement, including the case for returning IETs to service following the discovery of cracks in 2021.

Andrew spends a lot of time on coaching to allow his team greater autonomy, as well as developing engineers, mentoring, working with national industry groups on issues such as those that needed to be dealt with following the Carmont derailment, and on systems engineering within vehicles and the railway. Almost as a throwaway line, he also mentioned that he’s a fully qualified train guard and has been for 15 years.

Sage advice

Looking back on his career, Andrew’s advice to young engineers can be summarised as:

- Try lots of things. Some you might not fancy, but you may actually like. In any event, it will help you see the industry and start to form your own opinions.

- Do a mixture of things, e.g., technical, people, commercial.

- Get all the experience you can, most of it is useful at some time.

- Be aware of our history and where we have come from – it will help guide our direction.

- And, best of all, every day is a school day!

Andrew reflected on how safety has improved from his early days of short cuts to today’s safety culture, and stressed the importance of speaking up if you feel something is wrong.

In addition, it is vital that today’s railway engineers try and understand as much of the railway system as they can. As previous Chairs have said, the railway is a tightly integrated system and no one part of the system can function in isolation from the others.

Where are we now?

Andrew observed that the railway is at a crossroads. Since lockdown, passenger numbers have recovered quite well but farebox receipts are down and there are significant cost pressures in an industry with very high fixed costs. Moreover, we now have more interfaces in the industry than ever before, and each interface usually involves a price mark up! Perhaps of more concern, though, many of these interfaces contain safety risk.

There is huge potential for the railway. All the reports on decarbonisation highlight rail’s energy efficiency and the zero-carbon potential of an electric railway. If passengers and freight move to rail with its green credentials, rail will be further enhanced. However, to deliver the capacity required to accommodate all this, trains with better performance – something that strongly favours electric trains – will make the best use of the network’s capacity. Andrew quoted a Rail Delivery Group report:

“Travelling by train is more than a journey. It’s the greenest form of public transport, and the ready-made solution for a low carbon future where our roads are quieter and safer, and the air we breathe is cleaner.

“As Britain emerges from the pandemic emergency, we have a chance to pursue a cleaner, greener recovery. With the UK Government’s legally binding commitment to reduce carbon emissions, we must all play our part to achieve those goals – and so the rail industry is working hard to become even greener.

Put simply, taking the train already helps tackle climate change – it cuts carbon emissions by two thirds compared to traveling by car – and it can do more in future.”

Challenges

Andrew strongly believes that we urgently need to bring revenue and costs together avoiding perverse incentives with organisations acting in isolation. Some progress is evident through, for example, the GWR Alliance with Network Rail and the East Coast partnership.

He went on to say that we cannot remain in a world of cost cutting with no investment. We must tactically target investment for the benefit of the customers (passenger and freight). Andrew illustrated this through a quote from Rail Partners’ Track to Growth (July 2023):

“To ensure cost is not reduced to the detriment of revenue, it is essential to consider both sides of the ledger and the net impact of decisions. Considering cost and revenue holistically will help allow operators to begin closing the financial gap left by the pandemic and bring passengers back to rail in greater numbers.”

“Nearly five years on from the announcement of the Williams Review, and after a pandemic that turned the industry on its head, delayed reform is undermining rail’s ability to deliver to its full potential. Critical choices face the railway, including how we can bring more passengers back, make rail attractive against other modes, restore hundreds of millions of pounds in lost revenue, and ultimately set up the industry for long term success.

“It is widely recognised that the railway is not performing as it should, but the scale of the challenges is often underestimated. Getting back on the track to growth involves correctly diagnosing the problems facing the railway, putting to one side ideological debates about public versus private, and prioritising what works. If competition between train companies is harnessed in a reinvigorated public-private partnership for the railway, it will drive better outcomes for passengers and taxpayers.”

However, Andrew questioned whether Great British Railways is the right thing. He observed that if the train operators become one step removed from customers with Network Rail “in the middle”, then it is not. The service operator is best placed to understand their customers, but we still need a guiding mind and fewer interfaces whilst maintaining and improving safety.

Concluding with the priorities for his year as chair, he plans to focus on the importance of the people who shape our industry, the young people that will be our future. Although the railway is experiencing tough times, it’s a good time to join as it’s a good opportunity to help build the future. Growing capacity within the railway, and building its natural “green” USP, will be a significant contribution to the necessary drive for modal shift to contribute to UK (and global) net-zero.