When managing infrastructure risk, SFAIRP is an abbreviation for ‘So Far As Is Reasonably Practicable’ and ALARP is an abbreviation of ‘As Low As Reasonably Practicable’. This article will look at the difference between SFAIRP and ALARP, explain the legal implications and what good practice looks like.

Within the rail industry there are some who may wonder if the terms SFAIRP and ALARP mean the same thing or not. The Health and Safety Executive (HSE) provides good guidance on its website, which includes that SFAIRP and ALARP mean essentially the same thing. SFAIRP is the term most often used in the Health and Safety at Work etc Act 1974 (HASAWA) and in regulations, with ALARP being a term mainly used by people such as risk specialists and infrastructure managers. Infrastructure managers are referred to as duty-holders by the HSE.

The HSE’s view is that the terms SFAIRP and ALARP are interchangeable, except when drafting formal legal documents when then the correct legal phrase of SFAIRP must be used. ALARP is probably used by many as it is simpler to pronounce!

Both terms are based on the concept of ‘reasonably practicable’. This involves weighing a risk against the trouble, time, and money needed to control the risk, which is called the ‘sacrifice’ by the HSE. An important thing to note is that not having the required budget to control a risk isn’t within the definition of ‘reasonably practicable’. So the SFAIRP argument can’t be used just to simply save money.

Reasonably practicable

The reasonably practicable term has been enshrined in UK case law since the case of Edwards v. National Coal Board in 1949. The definition set out by the Court of Appeal in its judgment was:

“’Reasonably practicable’ is a narrower term than ‘physically possible’ … a computation must be made by the owner in which the quantum of risk is placed on one scale and the sacrifice involved in the measures necessary for averting the risk (whether in money, time, or trouble) is placed in the other, and that, if it be shown that there is a gross disproportion between them – the risk being insignificant in relation to the sacrifice.”

Quite simply, making sure a risk has been reduced SFAIRP/ALARP is about weighing the risk against the effort and resource to further reduce it. However, the decision is weighted in favour of health and safety because the presumption is that the duty-holder should implement the risk reduction measure. To avoid having to make this sacrifice, the duty-holder must be able to show that it would be ‘grossly disproportionate’ to the benefits of risk reduction that would be achieved. The process is not one of balancing the costs and benefits of measures, but of adopting measures – except where they are ruled out because they involve grossly disproportionate sacrifices.

A simple example is given in the HSE guidance. To spend £1 million to prevent five staff suffering bruised knees is grossly disproportionate; but to spend £1 million to prevent a major explosion capable of killing 150 people is proportionate.

Of course, in reality it is never as simple as this and many decisions about risk and the controls to achieve SFAIRP/ALARP are not easy, as we will show. Factors come into play such as ongoing costs set against remote chances of one-off events (which can be often the case in rail), or daily expense and supervision time required to ensure that, for another example given by the HSE, “employees wear ear defenders set against a chance of developing hearing loss at some time in the future”.

It requires careful judgment by safety experts. There is no simple formula for computing what is SFAIRP/ALARP, and it can get very complicated.

Including gross disproportion means that an SFAIRP/ALARP judgement is not a simple cost benefit analysis, but is weighted to favour carrying out the safety improvement. The HSE recommends that the bias towards safety “has to be argued in the light of all the circumstances applying to the case and the precautionary approach that these circumstances warrant”. More detailed SFAIRP /ALARP guidance is available from the HSE website.

The reasonably practicable test was enshrined in UK Law in HASAWA, as the duty to ensure SFAIRP. This was also when the HSE was established who then became the regulator for the HASAWA 1974. The regulations have evolved over time and there is now a considerable library of rail industry case law, and the concept of reasonably practicable has been well established in the courts.

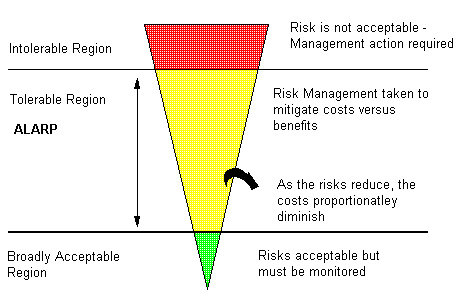

The ‘ALARP Triangle’ is a tool for determining risk tolerability that was created by the HSE. It is only a tool though and will not provide a definitive answer whether something is SFAIRP/ALARP. There are three ‘zones’ in the triangle:

Intolerable – the HSE consider any risks in this area too high and will not be accepted.

Tolerable if ALARP – in this area a case can be made as to why a risk is SFAIRP/ALARP.

Broadly acceptable – the risk is so low that it is not reasonable to spend additional time, effort and money looking for ways to reduce the risk further; but the risk must be managed in accordance with standards and good practice.

Broadly acceptable does not mean ‘do nothing’ and does not absolve anyone of their legal duties. If any reasonably practical measures are identified, they must be implemented.

Societal concerns

Societal concerns can arise when the manifestation of a risk impacts society as a whole. This often occurs when managing risk in the rail industry, as the impact of a serious incident can produce an adverse societal response. This can result in a loss of confidence by society in the provisions and arrangements in place for protecting people, and a loss of trust in the industry to control hazards. This might arise where large numbers of people are harmed at the same time and society having a greater aversion, for example, to an incident harming 10 people, than to 10 incidents harming one person each.

HSE considers that risk and sacrifice must be assessed in its social context. So as well as taking account of individual risk, HSE considers societal concerns. It says it believes it is right that the judgment as to whether measures are grossly disproportionate should reflect societal risk, that is to say, large numbers of people (employees or the public) being harmed at once.

Continual improvement

Even after a SFAIRP/ALARP case has been made, duty holders must carry out continual improvements. As technology develops, new and better methods of risk control become available. Duty-holders should review what is available and consider whether they need to implement new controls.

This does not mean that the best risk controls available are necessarily reasonably practicable. It is only if the cost of implementing any new methods of control is not grossly disproportionate to the reduction in risk they achieve. It may not be reasonably practicable to upgrade older equipment to modern standards. However, there may still be other measures that are required to reduce the risk to SFAIRP/ALARP. This could be by implementing partial upgrades or alternative measures.

Changes in knowledge about the size or nature of the risk presented by a hazard will also affect SFAIRP/ALARP. If there is evidence to show that a hazard presents a significantly greater risk than previously identified, then stronger controls may be required. However, if the evidence shows the hazard presents significantly less risk than previously assessed, then a relaxation in the controls provided and new arrangements could ensure the risks are still SFAIRP/ALARP.

Some organisations may implement standards of risk control that are more stringent than good practice. They may do this to meet corporate social responsibility goals or because they have agreed with their staff to provide additional controls. It does not follow that these risk control standards are reasonably practicable just because a few organisations have adopted them.

It must also be remembered that SFAIRP/ALARP does not represent zero when managing engineering risk. The risk arising from a hazard may occur sometime, even though the risk is SFAIRP/ALARP, which could result in harm. This may be an uncomfortable thought to some, but it has to be accepted that the risk from an activity can never be entirely eliminated, unless the activity is stopped completely. The “tolerability” of a risk is covered in detail in ‘Reducing Risks, Protecting People’ published by the HSE. This also goes some way to explaining why risk assessments need to feed into infrastructure risk contingency planning.