“The Government has clearly set out its firm focus on rebalancing the economy and creating jobs, skills and talent to raise the level of productivity across the UK. HS2 is essential to delivering these wider ambitions.”

“This Government is clear that HS2’s great potential for the whole nation continues to outweigh its costs. It will generate a vast increase in capacity, with thousands of extra seats, making life easier for travellers and better connecting our biggest cities. It has the potential to create highly skilled jobs, spread prosperity across the country and deliver world class transport infrastructure of which we can all be proud. It is now time to get on with delivering it.”

“Since its inception, Government has regularly restated the need for HS2. In 2013, the Department set out a comprehensive body of evidence illustrating the need for HS2; and this was restated again in 2015 and 2017. At each point an increasing weight of evidence has demonstrated the pressing importance for a step change in capacity to alleviate crowding problems on the existing railway, and the scheme’s potential to redistribute opportunity and prosperity more evenly across the country.”

These quotes are from the full business case for HS2 phase one, published in April 2020. This document makes it clear that HS2 offers economic benefits far greater than its cost. Moreover, it does not fully quantify all the benefits set out in the strategic case such as the transformative benefits from changes in business location decisions.

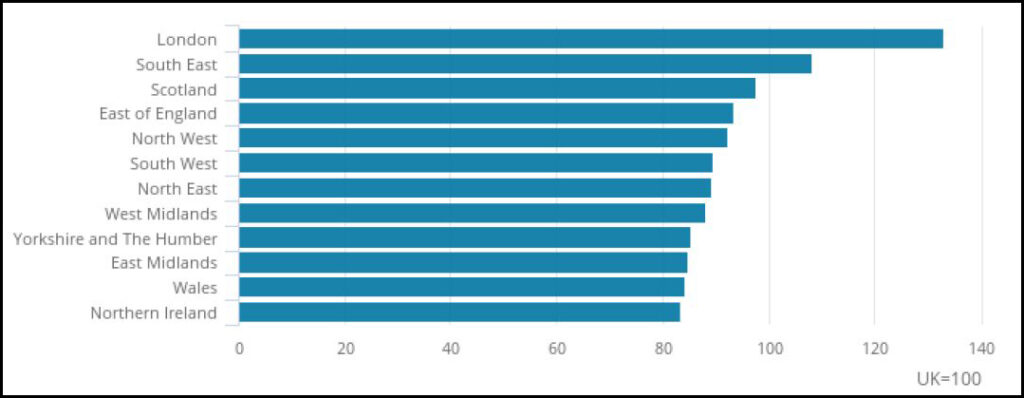

It also shows that, of the 30 countries in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), the UK ranks 24th out of 30 for regional economic disparities. Furthermore, it notes that the UK has a long running nominal productivity gap with the six other G7 countries and that this is largely due to the gap between London and other UK regions.

The business case notes that: “London’s success as a global city has been driven in part by the effectiveness of its transport system which allows the easy flow of skills, services, and products into and around the city.” It notes that government is keen to replicate the success of London’s transport network in the regions by improving connectivity between the cities of the Midlands and the North.

The above explains why, for over a decade, Government has consistently supported HS2. Yet since 2021, HS2 has been cut back and is now at risk of just being a line from Old Oak Common to Birmingham.

Why HS2?

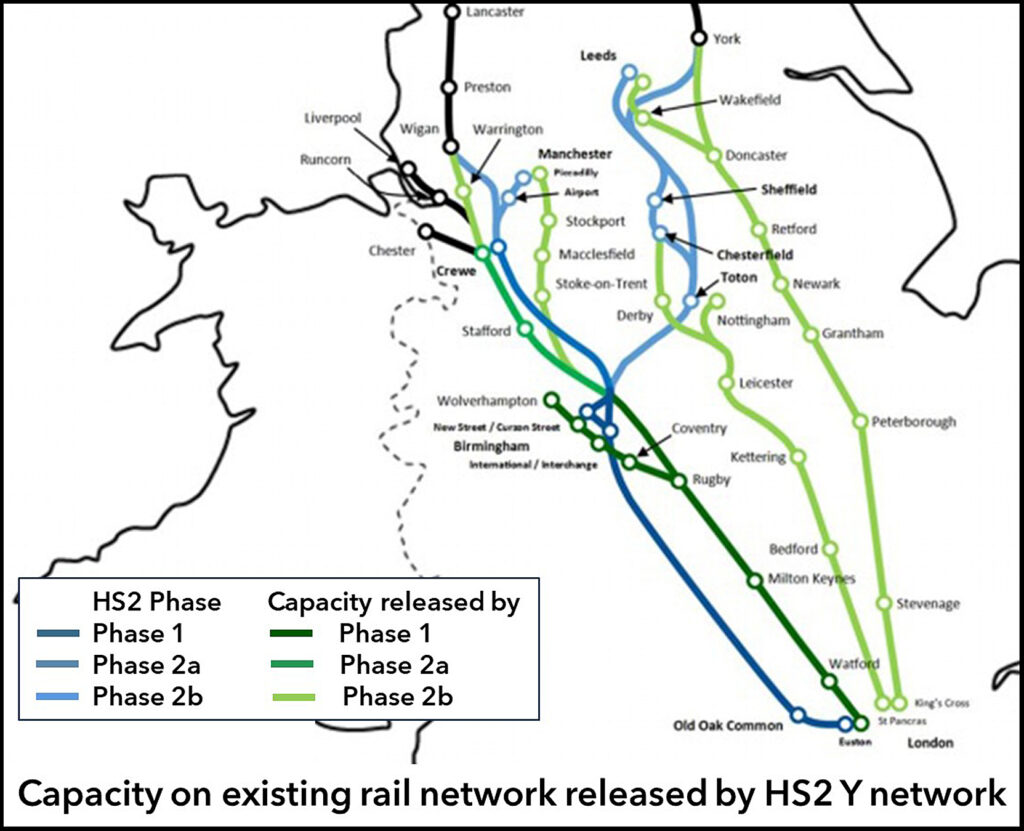

In 2008, Network Rail started a 12-month study on the long-term need for more railway capacity. This analysed a dozen options and concluded that a new high-speed line to relieve the West Coast Main Line (WCML) is needed. HS2 was established in 2009 to develop proposals for high-speed rail services. A year later, it had developed proposals for a Y-shaped network which would serve eight of the UK’s 10 largest cities. This network incorporated links to the West Coast and East Coast main lines for high-speed trains to additional destinations. It also served the East Midlands and South Yorkshire. In this way it would serve Britain’s largest cities and free up significant capacity for additional conventional passenger trains and freight on the West Coast, Midland, and East Coast main lines.

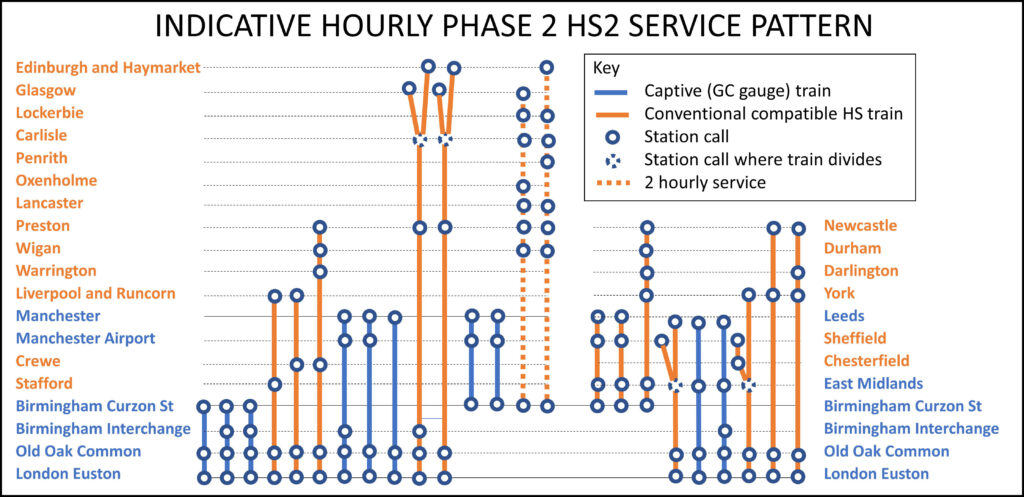

The first phase of HS2 is a line from London to join the West Coast main line north of Lichfield with a spur to Birmingham. This is essentially a by-pass for the busiest section of the West Coast main line. The initial train service plan had only a third of HS2 trains from Euston serving Birmingham. The remainder were to continue on the WCML to Manchester, Liverpool, Glasgow, and Edinburgh.

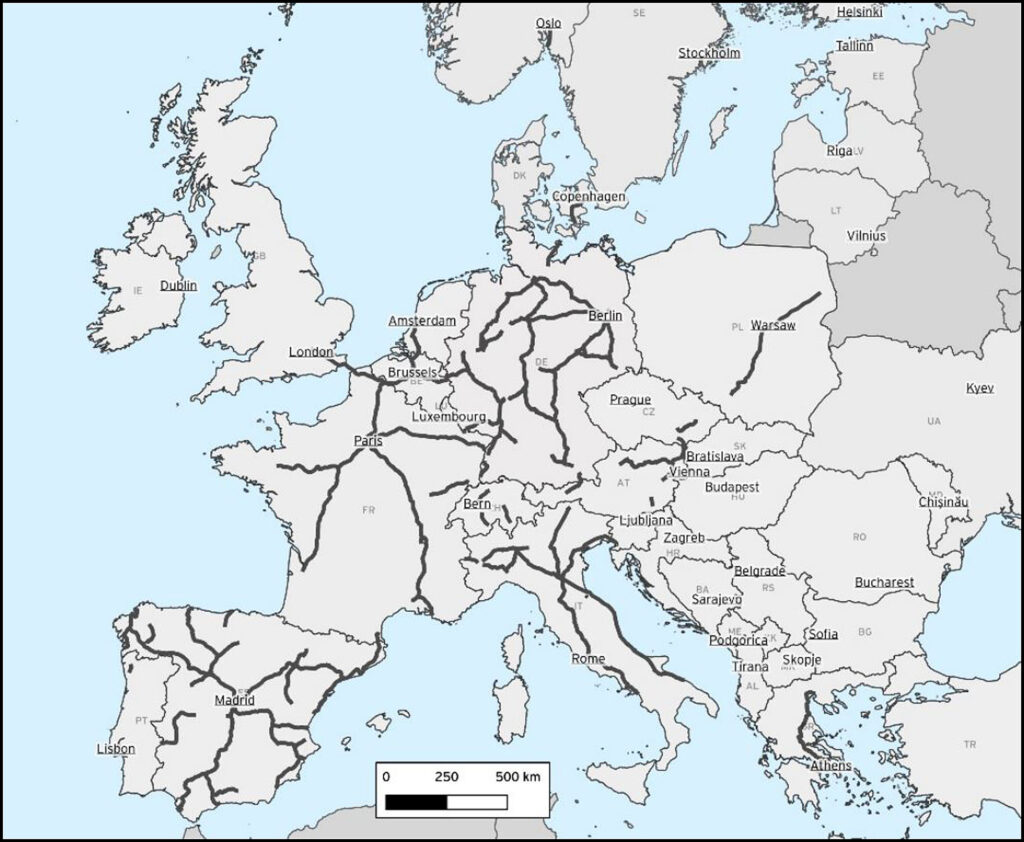

Until recently, all documents concerning HS2 published by Government and Network Rail emphasised that HS2 is the most effective way to provide much-needed additional rail capacity. There was also recognition that the UK lags behind the many countries in Europe and beyond which have recognised the massive benefits high-speed rail delivers in economic and environmental terms.

The rationale for a dedicated high-speed line is that it would be cheaper to build and considerably less disruptive than providing an existing rail route with additional lines. A recent Network Rail study found that upgrading the East Coast main line to provide the same capacity of the HS2 Leeds leg would require continuous weekend closures for many years.

The 2012 HS2 White Paper concluded that additional benefits from a high-speed line outweigh the incremental costs of constructing high-speed rather than conventional lines by a factor of more than four to one.

HS2 also offers huge environmental benefits as it creates the rail capacity needed for modal shift of passengers and freight from more carbon intensive transport modes. As HS2 is an efficient high-capacity electric railway, it offers particularly low emissions per passenger kilometre. The 2020 business case states that HS2 will offer lower carbon journeys at 8g CO2e per passenger kilometre compared with inter-city rail (22g), inter-urban car (67g), and domestic aviation (170g).

Route and specification

HS2’s phase one route is the most direct route between London and the West Midlands. It also passes fewer population centres than the longer and more expensive routes such as those along the M1 and M40 corridors. It does however involve a significant amount of tunnelling to get out of London and pass under towns in the Chilterns Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty.

Following consultation, the length of the line in tunnel, including green tunnels, was increased by 50% to around 36km. In addition, 90km of the route will be partially or totally hidden in cuttings. Hence over half of the 225km will be in tunnels or cuttings.

HS2’s design is based on proven technology. Its reference train was the 360km/h (225mph) Alstom AGV which entered service in 2012. This was used to establish the performance characteristics of the HS2 service. Compared with 360km/h, a 300km/h maximum speed would have extended London to Birmingham journeys by 4.5 minutes with longer delays to stations north of Birmingham.

Taking this, and other factors into account, it was decided that HS2 should initially operate at 360km/hr and be designed for 400km/hr to avoid permanently forgoing opportunities for future journey time reductions. Recently constructed high-speed lines from Strasbourg to Paris and from Milan to Bologna in Italy, also have alignments designed for 400km/hr. The route therefore had to be designed with a minimum radius curve of 7,200 metres. The minimum radius curves required for 300 and 360km/h are respectively 4,000 and 5,800 metres.

To maximise its benefit, HS2 phase one has been designed to ultimately support a train service to Birmingham and cities on its Western and Eastern legs. This requires a capacity of 18 trains per hour. This is to be achieved by the use of ETCS signalling and Automatic Train Operation. Infrastructure configuration, in particular the London Euston terminus, has been designed for this capacity which has been confirmed by operational reviews of converging and diverging junctions.

As it only carries high-speed trains, HS2 is, in effect, a high-speed metro and does not suffer from the capacity-destroying problems of a mixed train railway on which trains travel at different speeds. In part, this is why the original HS2 plan offers a large increase in passenger capacity. Due to this, and the capacity it releases on the WCML, HS2 could increase the peak-time seats per hour out of Euston from 12,100 to 31,200.

HS2’s trains are to be 200 metres long which can run coupled together to provide a train with 1,100 seats. The trains currently on order are classic compatible trains that can run on the conventional network. It was originally planned that, when the full Y network was built, half the HS2 trains would run only on the HS2 network which is being built to European GC loading gauge. Hence it was envisaged that a further order would be for trains built to GC gauge which offers the possibility of double-deck high-speed trains as run on the continent. However, dedicated HS2 trains are unlikely to be built for a cut-back HS2 network, so the cost of constructing phase one to GC gauge will be wasted.

Where did it go wrong?

In 2021, the Government published its Integrated Rail Plan which cancelled HS2’s Eastern leg to Leeds, leaving a spur to East Midlands Parkway. The Golborne link, which took HS2 to just South of Wigan on the WCML was cancelled in June 2022. At the time of writing, it is quite possible that Government will announce the cancellation of both HS2’s Western Leg to Manchester and that HS2 will be permanently terminated at Old Oak Common.

In all the discussion about HS2, the focus is on excessive costs with hardly any mention of its benefits. It is perhaps not surprising that Government Minister’s statements on this issue contradict or ignore previous Government pronouncements, made over many years, that HS2 is essential for rebalancing the economy and increasing productivity. The mainstream media also hardly mentions the transformation benefits that HS2 offers and focuses on costs that are said to be ‘eye-watering’ and spiralling ‘out of control’.

HS2 has some responsibility for this perception. Although it now actively promotes the benefits of high-speed rail, for years little was done to sell these benefits. As a result, the narrative that HS2 is a vanity project which is spending billions to save a few minutes off the rail journey between London and Birmingham took hold. For this reason, polls indicate that those who oppose HS2 outnumber its supporters by two to one.

Costs

HS2’s cost estimates have progressively risen since its first phase one budget of £16.3 billion in 2013 (at 2011 prices), as shown in Table 1. The current budget for phase one, including Euston, is £40.3 billion plus a £4.4 billion contingency. A 2020 National Audit Office report concluded that the DfT and HS2 underestimated the complexity of the programme and that HS2 did not account for risk and uncertainty in its early estimates.

One reason for the higher cost of the 2019 estimate was the unforeseen extent of changes required by MPs as Parliament considered the HS2 Bill. This required a 50% increase in the amount of tunnelling and additional cuttings to lower the railway. HS2 consider that such environmental mitigation made HS2 £1 billion more expensive than comparable European high-speed lines.

Detailed costs for the truncated Y network are currently not clear as phase 2 is at a very early stage. In 2019, the DfT estimated that the costs of the full current HS2 project would be between £65 billion and £88 billion at 2015 prices.

These costs are now significantly higher as construction inflation has increased the costs of new work by 24% since 2019.

In March, Government decided to rephase HS2 construction by halting work at Euston station to develop an affordable design and rephasing construction of phase 2a between Lichfield and Crewe by two years. While this decision will reduce the annual cost of HS2, it will inevitably increase its total cost.

After various studies had shown that UK projects are typically 10-30% more expensive than those in Europe, in 2014 the Government commissioned a high-speed rail international benchmarking study.

| £ billions | ||

| 2013 | 16.3 | Basic estimate prepared for business case. |

| 2015 | 27.0 | For hybrid bill on basis of route drawings. No ground investigation. |

| 2017 | 37.0 | After hybrid bill route finalised route, limited ground and site surveys, estimate comprised 15,000 lines of data. |

| 2019 | 44.4 | Prior to start of construction after 80% design complete with input from contracts, estimate comprised 260,000 lines of data. |

This looked at 32 comparator European high speed rail schemes and was overseen by an expert panel chaired by Sir John Armitt. It included a detailed comparison which found that HS2 phase 2 was 49% more expensive than a European high-speed line with very similar characteristics. It found that the factors that accounted for this additional cost were:

- Strategic objectives requiring greater capacity and more intermediate stations (7%).

- Limited capacity of UK rail infrastructure requires dedicated high-speed lines into city centres (15%).

- Fragmented UK construction industry and continuity of work (12%).

- Onerous design requirements (5%).

- Scope development compounded by limited experience of delivering high-speed rail in UK (10%).

It was recently reported that sources close to the Prime Minister advised that HS2 costs were “spiralling out of control” and that HS2 bosses were “like kids with a golden credit card”. While this is good fodder for the tabloid newspapers, the above shows that the reality is more subtle.

It is certainly true that there is scope for savings. However, construction inflation is at its highest level for decades, though as costs go up, so do the benefits. Moreover, the loss of momentum due to Government indecision and delaying progress also has an enormous impact on costs.

Although Government finances are under severe pressure, a distinction needs to be made between general spending and investment. For over a decade, it has been Government policy that HS2 is essential if the economy is to be rebalanced and regional productivity improved. Government borrowing to fund investment in HS2 should therefore be regarded a profitable investment.

What might have been

Sadly, now that HS2 phase 2 to Manchester has been cancelled, the vision of this article cannot now be realised.

The full HS2 Y network was a major project that has been 15 years in the planning. During this time, cities and Network Rail have spent much time and money preparing for HS2 phase two. Now, the Government’s command paper “Network North – Transforming British Transport” claims the £36 billion to be spent on HS2 phase 2 is better spent on a package of transport projects. The hastily prepared nature of this plan is evident by its proposal to extend Manchester’s tram network to the city’s airport despite this line opening in 2014.

This paper seeks to prioritise worthwhile intra-city transport investment, such as a West Yorkshire mass transit system, over HS2. Yet both should be regarded as profitable investments to be funded by borrowing. Moreover, there is no timescale for the delivery of Network North. If this is to be funded by HS2 phase 2 savings, this implies that the projects will have a similar spend profile with most expenditure to be incurred in the 2030s. Yet the command paper claims that “we’re releasing a tidal wave of new investment into hundreds of projects.”

It justifies cancelling HS2 phase 2 as the facts have changed. The pandemic is said to have significantly changed travel patterns. Yet anyone travelling on long distance services knows trains are full. LNER passenger numbers, for example, have now exceeded pre-Covid levels. It also claims HS2 phase 1 is five times the cost of equivalent schemes in Europe. Yet the previously mentioned high-speed rail cost comparison study actually stated that HS2 costs 49% the cost of a comparable European high-speed rail project.

HS2 phase 2’s cancellation is irrevocable. The land purchased for it is to be sold, the route will no longer be safeguarded, and a downsized terminus at Euston will permanently constrain the number of trains. Though the command paper’s commitment that HS2 phase one will terminate at Euston is some small comfort, the way this has been specified is further evidence of the shallow thinking.

A huge sum of money is being spent on HS2 phase one which will enable high-speed trains to by-pass the first 186km of the WCML from London or go to Birmingham. This line is designed for 18 trains per hour (tph) for which it was considered that Euston needed 11 platforms. After cancelling HS2 phase 2, the key issue for the remaining HS2 network is its service pattern. As shown by the diagram, delivery of the originally proposed services to Birmingham, Liverpool, Manchester, Preston, and Glasgow / Edinburgh requires 11 tph.

The command paper does not address this point and just specifies that Euston will have six platforms, which is certainly insufficient for anything like 11 tph. The priority is thus to build HS2 Euston as cheaply as possible. This decision is economic vandalism as it saves, perhaps, 10% of the cost of HS2 phase one whilst, say, halving its benefits.

The issue of only considering costs, and not benefits, was highlighted by former Minister of Transport Patrick McLoughlin who, in a particularly apt quote, stated:

“Of course, there will always be pressure to look at costs, and to make sure we’re getting the best value for money – it would be insane not to do so. But it would also be insane not to say, ‘what is our transport system going to look like in 30, 40, 50 years’ time?’ and to make sure our great cities have those same opportunities that London has, and make sure that young people look to those cities to base their lives on, and not to move away from them.”

Image credit: Hs2 Ltd.