The Greater Paris project seeks to transform the French capital from a monocentric city to a multipolar metropolis. At the heart of this ambitious plan, combining urban and economic development, is the Grand Paris Express, a new-build automatic metro designed to link up and breathe new life into the Paris suburbs and beyond.

To dig deeper, Rail Engineer met with Alexandre Missoffe, managing director of Greater Paris Investment Agency, which has several tasks on its hands. In addition to tracking and encouraging investment, both within the Paris region (Ile-de-France) and in the construction project itself, it also liaises with other cities worldwide.

“From London to Singapore, Toronto, Hong Kong and Moscow, we are all exploring ways to make our cities sustainable with affordable housing, an efficient economic situation, clustering activities,” explained Alexandre Missoffe. “The fundamental nature of the issues we are facing is the same: how to expand our cities without pushing people too far outside the centre? How to resist urban sprawl without creating too much urban density?”

Given these interests in common, the cities are working to create a network for sharing their experiences, know-how, news and views. “We meet at events and organise them too,” he added. “For instance, our Agency organises tours of the Greater Paris region for foreign visitors, like the mayor of Toronto, for example, who came over in October 2019 to see our new solution for affordable housing. Then, in November 2019, we were in Hong Kong to meet with MTR (Mass Transit Railway, the local public transport network). This engagement with our foreign counterparts is extremely important.”

Think tank

Another mission for the Agency is acting as a kind of ‘think tank’ for governments and companies at local and national levels, both pushing for and carrying out proposals to boost the appeal of the Greater Paris region. As an example, the Agency is exploring the challenges of energy sustainability.

“By 2030, the total energy needed to power the Grand Paris Express, plus all the new housing and industrial activities under the Greater Paris umbrella, will represent the output of three nuclear power plants!” Alexandre Missoffe said.

“Of course, we won’t be building these plants – the energy won’t be produced within the Paris region, but sourced further afield,” he hastened to add.

However, for companies such as manufacturers in the auto industry, for instance, the cost of energy rather than salaries is more of a priority. This is down to latest generation 4.0 factories that require fewer workers but more and more computers, robotics, machines and equipment that consume a lot of energy.

“So, if you are a car manufacturer or a company in a high energy consuming industry, the cost of energy is a key criterion when deciding where to locate your business,” explained Mr Missoffe. “Today, they have to anticipate increases in energy demand and are looking for an affordable, carbon-free and safe energy supply system for the decades to come. Hence, the reason we are working on this strategic topic, amongst others, with the French Government.”

Innovation, time and risk-taking

“If we were to build the Grand Paris Express we are building today 100 years from now, it wouldn’t be cheaper or quicker, and probably not better,” reckons Mr Missoffe. “This is one of the great paradoxes of innovation in the construction industry.”

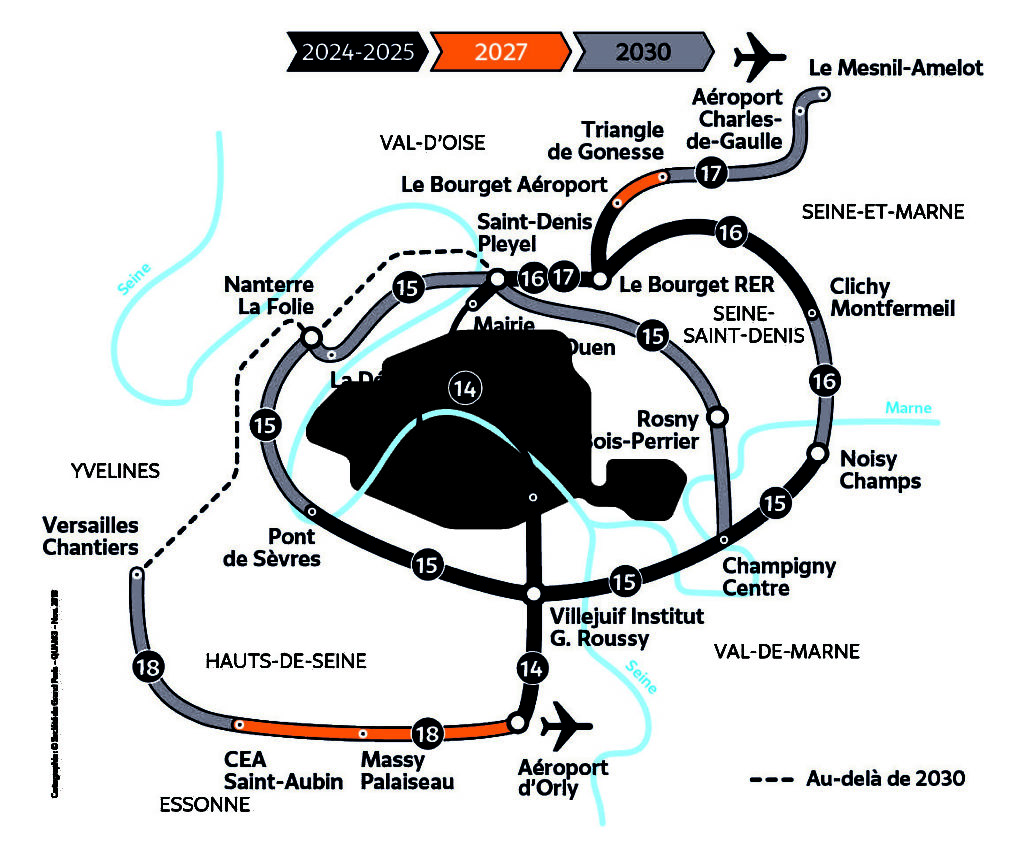

Building the Paris Metro was approved in 1898 and the first line opened in 1900, 15 months later. But, for this latest transport system, the law was adopted in 2010 and the first line, a section of Line 16, is scheduled to open in 2024. Why so long?

“There’s a tendency to be more risk averse for the core structural elements of all major construction projects, like Greater Paris, that involve large sums of public money, that are on tight deadlines and are very much in the media spotlight,” believes Mr Missoffe. “The people and companies involved in the project don’t want to be the ones responsible for a major delay or accident. Consequently, when given the choice between one technology or technique that seems to go faster, is cheaper and better, and another that has been proven over the past 15 years, they tend to opt for the latter.”

“Some new technologies were used when tunnelling Line 14 of the Paris metro under the city and there were issues,” says Mr Missoffe. “Most memorably in 2003, when the playground of a school in the 13th district of Paris [south of the city] collapsed!”

Fortunately, this incident occurred in the early hours of a Saturday morning, so nobody was hurt. However, all the engineering firms who worked on this line are now working on the Grand Paris Express. Bearing in mind the risk, they are naturally tending to stay on the safe side by using proven technologies.

“In my view, it’s absurd to build a network for 2030 using technologies that are decades old,” commented Mr Missoffe. “Surely we should be exploring next generation innovations for 2050.”

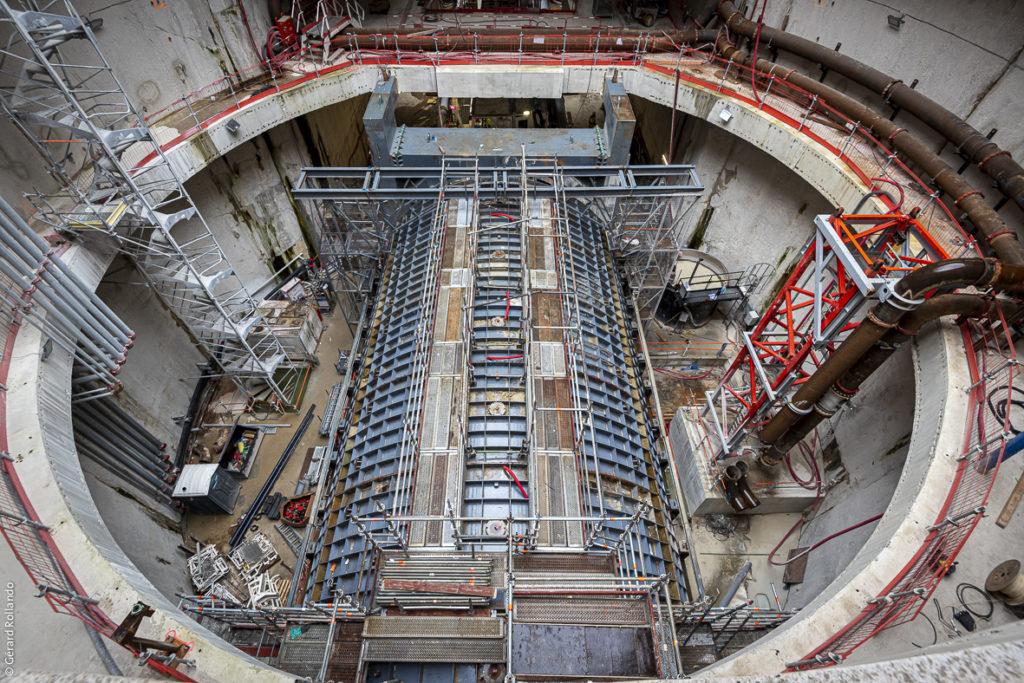

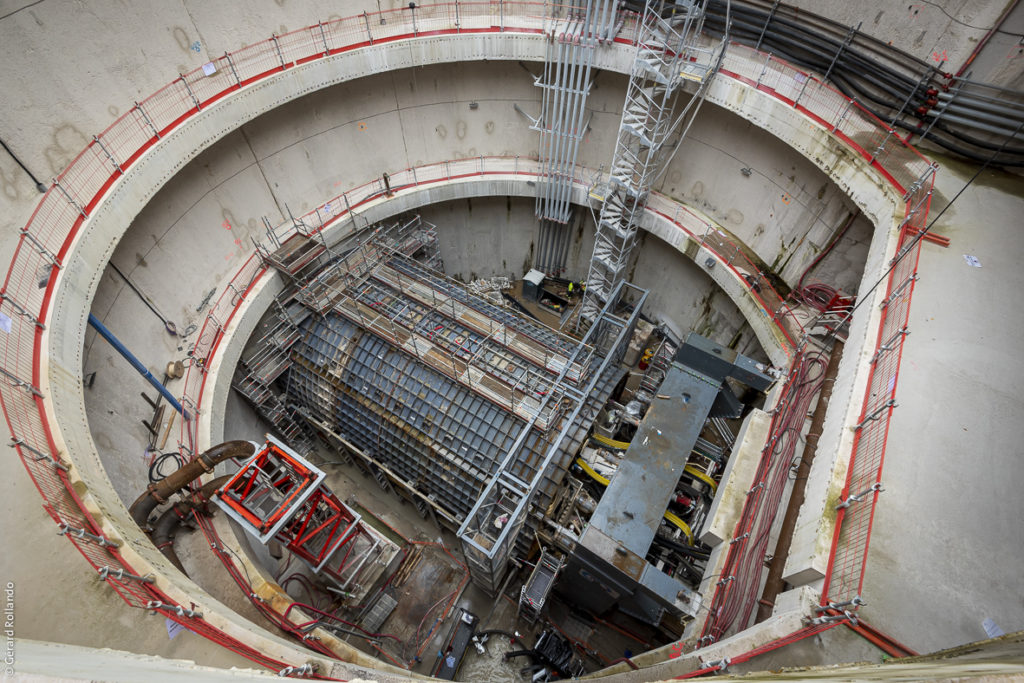

On the upside, however, he pointed out how this risk aversion doesn’t rule out innovating in other, less ‘risky’ areas, such as regenerative braking for the metro trains and geothermics, re-using tunnelling waste, testing new types of fibre-reinforced concrete, or boring with a Vertical Shaft Sinking Machine to save time and space.

Mountains of paperwork

The construction schedule is also being impacted by today’s stringent safety regulations and labour laws, “mountains of paperwork”, environmental obligations for protecting fauna and flora, and efforts to disrupt inhabitants as little as possible. A far cry from the ‘good old days’ when constructing Line 1 of the Paris network.

“Back in the day, they literally cut Paris in half for 15 months to build using the cut and cover method,” pointed out Mr Missoffe. “Today, creating such massive disruption to Parisians is totally out of the question!”

But, as he rightly points out, all these constraints are not unique to the Greater Paris project, but a tendency for all major construction projects.

Laying down the law

To a certain extent, special legislation has helped overcome some loopholes that might otherwise have slowed up progress even further. In 2010, the French Parliament passed a law, the Greater Paris Act, granting special powers, including for expropriation.

According to French law, the subsoil under a property right down to the centre of the earth belongs to the property owner. When tunnelling under it, constructors generally pay compensation of around three euros per square metre. However, when apartment buildings are involved, with multiple owners, the process becomes more complicated.

“You divide the compensation between the flat owners, but if any of them disagree, you have to settle in court,” explains Mr Missoffe. “Now, bear in mind we’re talking about tunnelling under 20,000 properties for the Grand Paris Express, the majority of which are apartment buildings. Imagine the time, the number of lawyers and judges, and money it would have taken to settle all the compensation disputes. It would take years!”

Fortunately, the new decree waives the obligation to make payments to property owners when tunnelling at a certain depth. Above this level, even if the volume of subsoil in question is technically worth just one euro, it pays out a minimum flat rate of €2,000. Problem sorted?

“Well, yes, this part of the construction might well have posed a challenge, but fortunately we anticipated and resolved it,” said Mr Missoffe.

Money matters

The Greater Paris Act also created the Société du Grand Paris (SGP), a special purpose body that manages the project and directly receives revenue from three taxes to reimburse the debt.

“In other words, this income, which amounts to around €700 million annually, can’t be used for any other purpose,” he explained. “Back in 2014, construction works had not started but the Société du Grand Paris was already provided with around four billion euros, a large amount exclusively secured for the future metro. The money is now spent, creating a debt that will be gradually paid off.”

Jobs to build, and beyond…

Who’s awarded the contracts to build the Grand Paris Express? “People might think that, since it’s a state-funded project, French firms get preferential treatment. But this isn’t the case,” Mr Missoffe insisted. “There’s so much work that we need both French and foreign companies to meet the deadlines. Indeed, major parts of the project have been allocated to foreign companies and the French are happy about this because they need these partners. Plus, they get to benefit from their expertise, know-how, and skills.”

At the same time, he says, the skills for building transport infrastructure are really lacking and becoming increasingly rare. Furthermore, Greater Paris is competing with other global cities to attract the best workers.

“There are many other major projects planned or ongoing over the world, like Crossrail or Rail Baltica, so we are competing with our counterparts to attract the best talents,” he explained. “While engineers may well want to work for us, they might get offered a 20 per cent salary raise to join another project. So yes, it’s a question of money and quality of life, but, most importantly, we are seeing a shortage of engineering talent for tunnelling work on major infrastructure projects.”

In addition to the jobs created to build the Grand Paris Express, once up and running, it is expected to significantly open up employment opportunities in the region. Line 16, for example, will provide a link between Clichy-sous-Bois, a suburb to the east of Paris with the highest unemployment rate in France, and Charles de Gaulle airport to the north. “There are thousands of jobs linked to the airport hub and logistics activities, but they can’t find people to fill them,” complained Mr Missoffe. “This is largely because people can’t access the jobs, since there is no transport infrastructure.”

There are currently 2,140,000 inhabitants in inner Paris and two million jobs. “This is ridiculous! The right balance is one job for every two inhabitants,” he exclaimed. “But today, because of this imbalance, plus the fact that the current transport systems (Metro and RER commuter rail network) are radial and all feed into the centre of Paris, too many people are travelling in and out of the city to work.”

This explains why much is riding on the orbital Grand Paris Express, which should encourage more people to live and work around Paris, and so relieve stress both on themselves and the existing transport systems.

Staying the course

For the Greater Paris Investment Agency, keeping the initial vision in its sights is one of the big challenges ahead. “If we lose this vision, the project will become just the sum of many parts. There is a danger of skipping some parts of the whole so, at the end of the day, Greater Paris no longer makes the sense it should,” Mr Missoffe reckons. “Of course, we must adapt the vision approach over time, but always bearing in mind where we want to go with Paris for the next 200 years.”

Fortunately, support for Greater Paris has remained constant despite political shifts over the years. “The project was launched by President Nicolas Sarkozy in 2009, then President François Hollande followed in 2012. While the latter certainly didn’t agree with a lot of what his predecessor had said and done, he kept the project on track. As has President Macron today.”

The 131 local communities making up the Greater Paris region support political parties across the political spectrum. Yet, according to Mr Missoffe, they all vote unanimously for every proposal concerning the project – the Grand Paris Express and urban development plans. “Everyone is in favour, regardless of their agendas. They might disagree over the details of a proposal, of course, but nobody wants Greater Paris on hold.”

Mr Missoffe summed up: “Paris and its region, Ile-de-France, currently generates one third of the country’s GDP, which is already massive. If the Greater Paris project works out, it will create employment, boost the attractivity of the region, and encourage new activities to locate here.”