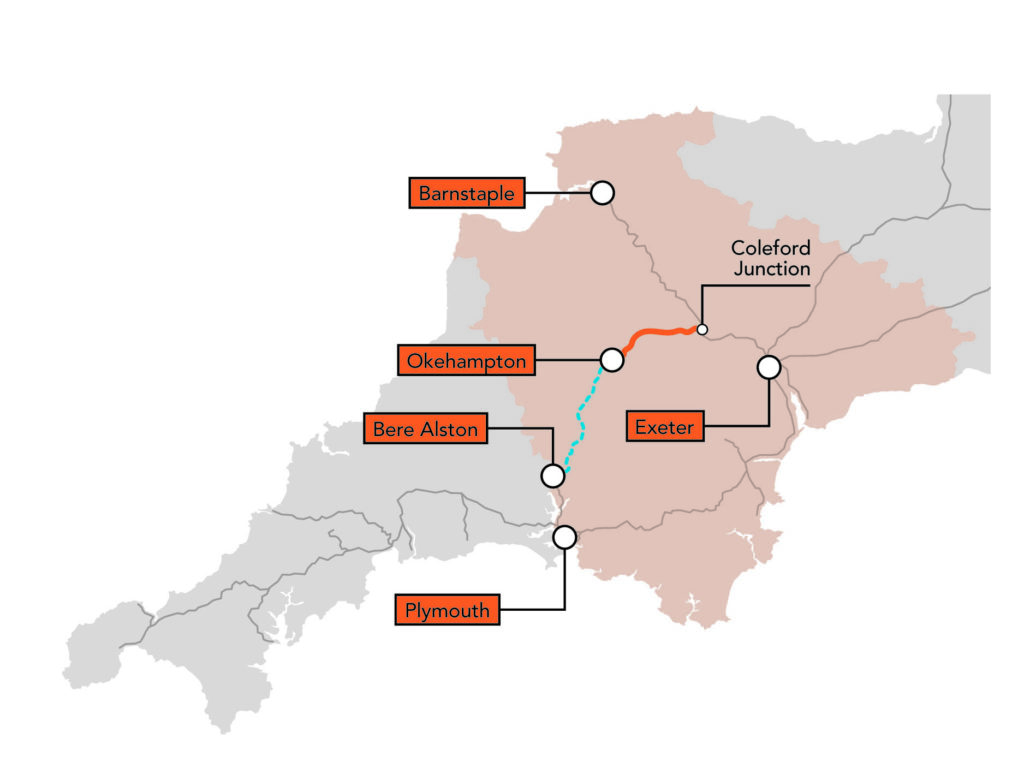

It’s always a delight to write about reopening a railway to passengers. It’s nothing to do with nostalgia; it’s all about releasing the potential to local communities, tourism and commerce, which is all relevant when considering the planned rebirth of the line from Okehampton to Coleford Junction, a 14-mile single-track route that links Okehampton and surrounding north Devon areas to Exeter and beyond.

The route was closed to passengers in 1972, 49 years ago. However, it was kept open to enable freight trains to maintain access to Meldon Quarry which, over the years, has provided high-quality track ballast for the railway network. The quarry closed in 2005 and the line was confined to occasional charter trains running as a Sunday Special, ensuring that the route was not completely forgotten.

The original line continued beyond Meldon Quarry, down to Bere Alston and eventually to Plymouth. It crossed Meldon Viaduct – now a Scheduled Monument – which soars 151 feet above the valley and comprises six warren truss spans supported by five lattice trestles.

Over the years, problems with the Dawlish sea wall have prompted discussion about this line’s reinstatement as an alternative route into Cornwall, but I am drifting into subject matter worthy of a different article.

Long term campaign

I met with Daniel Parkes, Programme Director for Network Rail, responsible for the work involved in reopening the line to Okehampton Station. He reminded me that there has been a long-term campaign by the Oke Rail lobby and other supporting bodies to develop plans to revive the line. Recognising the potential benefits of such a venture, about 12 months ago Network Rail procured the services of AECOM Design consultants, based in Bristol, to carry out a structural assessment of all assets on the existing railway.

The study concluded that 11 miles of track would have to be renewed. More than 40 cuttings and embankments were identified for work, with five in very poor condition. There were 11 level crossings, of which three have been closed. Network Rail is looking to upgrade six others with Miniature Signal Lights and there is the potential to close the remaining two. However, significant work will probably be needed to bring the crossings up to current standards.

Longitudinal timbers

Amey acted as resident engineer for the inspection of the structures, of which there are 60 bridges and culverts. The company carried out visual and detailed inspections of them all. Minor structural work was required on most of these structures. The longitudinal timbers on one bridge with needed replacing, along with the supporting structural members.

At the time I met Daniel, he explained that all this activity was progressing according to plan, alongside the level crossing work and an additional 14km of fencing that has to be replaced.

Linbrooke Services was responsible for installation of a GSM-R driver-signaller communication system which enables train drivers to speak directly with the signaller and control, thus removing the need for much of the traditional lineside equipment.

Okehampton is close to Dartmoor in the middle of Devon’s lovely countryside. There were potentially many environmental issues that Daniel and his team would have to take into account as they knew that they would be disrupting a considerable amount of natural overgrowth, as well as badgers, nesting birds, goshawks and pheasants to name a few (but apparently no newts).

A depot and compound was set up at Exeter Road Industrial Estate, located two miles west of Okehampton Station. It was designed to act as a hub for managers, supervisors, technical and project teams – as well as visitors – and was designed to help keep traffic off the country lanes, ensuring that everything would be provided on this site.

The value of the scheme is approximately £40M which includes the activity outlined above and the track renewal. Replacing single-line track can be quite complex logistically.

Good drainage

The first priority was to sort out the track and lineside drainage, enabling the formation to dry out. Years of vegetation growth and silting had to be removed. Road-rail vehicles equipped with digging, flushing and vacuum equipment were used to remove and expose the old drainage system, allowing the necessary repairs to be carried out.

The Railvac proved to be particularly useful, helping to clear the significant volumes of silt away from the formation. Also, Daniel was keen to point out that local landowners and neighbours have been particularly helpful and supportive whilst all this work was in progress. They clearly understood the benefits to the community that the reopened line would bring.

Once the drainage work was completed, 22 miles of rail was delivered using CWR trains, placing the rail alongside the existing line on one side. This was not a straightforward part of the process because the existing track consisted of components going back to 1922. Some sections were not in a healthy state and a judgement had to be made regarding the track’s ability to carry the weight of the CWR trains without incident.

Strengthening old track

There was some concern about the quality of the existing Bullhead track which, in places, dated back to 1927. Would it be able to withstand lateral forces from engineering trains? So, to reduce the risk of gauge spread, a decision was made to install in additional wooden sleeper after every existing five. This is not an exact science, so would it be adequate? Well, experience and good judgement prevailed and 130 continuous welded rails were delivered without incident.

Road/rail vehicles were then used to cut the existing track into 3m sections which were stacked five high to the side of the formation. A procession of bulldozers and excavators was used to remove the top ballast, consolidate the formation and calculate/mark a centre line for the new track.

More than 26,000 sleepers had been stockpiled at the Okehampton compound and the CWR was now lineside. So, how do you put it all together? By using an NTC, which stands for New Track Construction train and Balfour Beatty owns two of them.

Conveyor-belt renewals

The company was invited by Network Rail to install the 11 miles of single-track railway. The NTC is definitely an impressive piece of machinery. It is in fact a conveyor belt, with the sleepers being fed onto the machine by gantry from a sleeper train at one end and then placed with the correct spacing on the formation at the other. Then the CWR – which is now located either side of the NTC – is fed into the sleepers and clipped-up leaving a fully-functional railway line ready to receive ballast and for the rails to be destressed.

The NTC machine works with a team of eight fully-trained operators. Communication is critical because it is a continuous process that requires everything to work according to plan and, when that happens, the machine is able to install 400m of completed track in an hour. Daniel and his colleagues planned the work so that the sleepers stockpiled at Okehampton could be delivered to the machine without external influence which ensured that they were in control of every aspect of the relaying process.

Well, that was the theory and it worked very effectively almost all the time. Occasionally, of course, Murphy’s Law intervenes. The renewal work was carried out in four stages, working from Coleford Junction toward Okehampton. Each one was to take place in a week, with Stage 1 being 3km, Stage 2 – 6km, Stage 3 – 4km and Stage 4 – 3km. Once the NTC had finished its work, additional ballast was dropped to stabilise the track which was then tamped and aligned before restressing.

Hot in April?

The first stage was planned in April – a month not renowned for its hot weather – so it was decided to weld the CWR beforehand at the lineside, only to be confronted with record-breaking temperatures for April, in the high 20s Celsius. This had an impact on the stability of the track laid, so welders had to quickly introduce a number of joints to avoid any buckling. The team then reverted to welding all the CWR at the end of the relaying process, before destressing the track.

That minor incident aside, all has worked to plan and the completion date of December 2021 looks to be achievable. So who knows, maybe a Christmas Santa Special to Exeter – Covid permitting – will be an option for those who live in north Devon.

At present there is an intention to carry out some additional building work at Okehampton Station. However, there are no other plans to reopen old stations or build any new ones on the route. But a proposal is being developed for a new Okehampton Parkway Station and, who knows – as I alluded to at the start of this article – Bere Alston to Tavistock might not be too far away, which could in turn resurrect possible links with Plymouth and a second route into Cornwall. This, of course, would all depend on how the Dawlish sea wall behaves over the coming months and years.

Meanwhile, for college students, businesses and the Devon tourist industry, the Okehampton extension must be a huge boost to the local economy, environment and the railway network. Good news for everyone.