Shugborough Tunnel is located between Stafford and Rugeley in Staffordshire, on the edge of Cannock Chase. It takes the West Coast Main Line beneath the National Trust’s Shugborough estate. Built in 1846-47 by the Trent Valley Railway, it is 710m in length and aligned on a 1.5km radius. The tunnel featured in Rail Engineer (Issue 100, February 2013) when the track was relaid and lowered over Christmas 2012.

In common with most 19th century tunnels of any considerable length, its temporary works included shafts sunk along its alignment to enable excavation on multiple fronts. These were all unlined, passing through the Triassic pebble conglomerates and sandstone of the Kidderminster Formation. On completion, they were capped near the top with timber baulks and decking.

The shafts have deteriorated over the 170 years following construction and slight surface settlement had been identified at some, resulting in them being fenced off for safety reasons.

Network Rail made this one of their priority schemes, investing heavily to remove any risk of a collapse of debris into the tunnel. As part of its programme to deal with hidden shafts, the company engaged consultants COWI to locate and investigate the shafts; thereafter a solution was designed to secure and stabilise them, making the tunnel safe for future generations.

Construction and as-built records were patchy and inconclusive. However, COWI was able to use these desktop studies – together with the depressions at ground level and indications from brickwork jointing in the crown – to identify eight shafts. At each one, trial drilling and endoscopes were used for verification and inspection purposes. Seven shafts were soon confirmed, but the last one proved elusive and was only finally tracked down in early 2021, eight months after construction works started on site.

The shafts – up to 30m in depth – were found to be in good condition, but not uniform in size, varying in diameter between 1.8m and 3m. During test drilling of the tunnel lining, a void was identified between the brickwork and rock. COWI’s solution was for a project to drill and grout each shaft, and infill the lining void. The contract was awarded to Story Contracting’s Rail division in 2019.

Filling the voids

An early proposed solution was to use cementitious grouts behind the tunnel lining and water-based polymer grouts for the shaft infill. Cementitious grouts are relatively dense and the temporary loading of wet grout on the lining could have resulted in structural damage. Both grout types – being water-based – also bring the problems of disposal and water leakage through the brickwork, potentially contaminating the ballast or drainage.

By coincidence, Geobear gave a CPD (Continuing Professional Development) talk to Story Contracting and it was quickly identified that the company’s closed-cell polymer grouts could provide the solution, being lightweight and fast curing, offering controllable spread and not water-based.

During early contractor involvement, Geobear worked with COWI and Story Contracting to develop a solution for Shugborough Tunnel’s problems. There are no formal codes of practice or design codes covering these products, but Geobear was able to share its 40-year experience and technical knowledge to provide COWI with confidence in the product and proposed application.

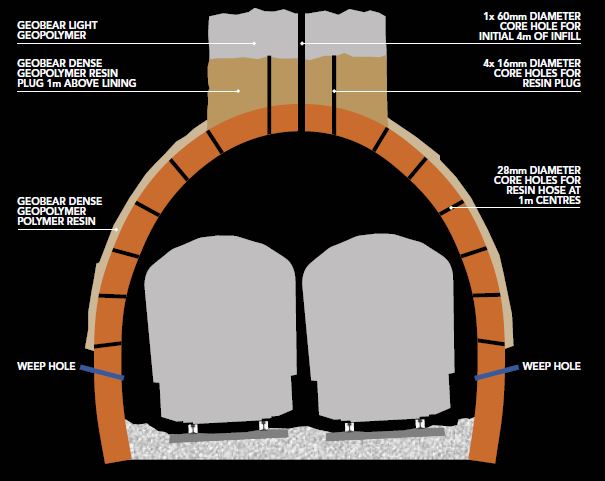

The agreed solution involved the use of a dense geopolymer to fill the void around the lining beneath each shaft and the first 1m above the shaft base. Lightweight geopolymer would be used to mass fill the remainder.

Global ground engineering

The Geobear company, formerly Uretek, was the inventor and pioneer of geopolymer technology that provides advanced and accurate systems for floor and foundation relevelling, ground stabilisation, as well as void filling and water sealing.

The controllability of geopolymer injection and its rapid curing – just 10 minutes – makes it very suitable for railway works in short possessions and has been used by its 70-strong UK workforce to relevel and support slab track in depots and on the Midland Main Line near Kentish Town. It was also trialled in Network Rail’s Upholland Tunnel in 2020.

The firm’s polymer materials are well proven, with over 200,000 successful projects in 40 years.

Stabilising the shafts

Richard Holmes, Geobear’s Managing Director for commercial and infrastructure projects, explained to Rail Engineer that the project began on site in May 2020 and delivery was planned in 27 ‘Rules of the Route’ Saturday night possessions of 8½ hours’ duration, but each effectively offering only five working hours.

The track access point was close by, just 300m west of the tunnel. All Geobear’s plant and equipment was contained with two 20-foot shipping containers, loaded onto rail trailers by telehandler and hauled into the tunnel using road-rail excavators. Work access was provided by two MEWPs (Mobile Elevating Work Platforms). Access to the shaft-top locations – across National Trust land – was established using aluminium trackway and work platforms to avoid damage.

The works were delivered in three stages at each shaft. Firstly, the void behind the brick lining was grouted 5m either side of the shaft, through a grid of holes at 2m centres longitudinally and 1m transversely. In the crown, the works were hampered by overhead line equipment, but works were completed around these without diversion. Around the perimeter of the area, holes were at 500mm centres. These were grouted first, using a dense geopolymer, to provide a bulkhead against which the subsequent grout would be injected. Grouting was restricted to 4 bar injection pressure to reduce any risk of damage to the lining.

Secondly, four grout holes were drilled through the lining into the shaft and further grout-injected to seal the base of the shaft, binding any debris sitting on the lining. A single 60mm diameter hole was drilled to inject a lightweight geopolymer higher into the shaft, filling the first 4m to form a plug.

Finally, from surface level – with the machine positioned well back from the shaft – Geobear drilled at 45º into the shaft tops, entering at up to 6m depth. This hole was then used to inject more grout in a single pour to completely fill the shafts. Up to 80m3 was needed per shaft.

During drilling for the lining grout holes, it was discovered that the voiding behind the lining greatly exceeded the anticipated 50mm average, with some being up to 500mm; the average was 135mm. As a result, Network Rail extended the contract to allow for this additional volume of grouting and, ultimately, 48 possessions were required rather than the planned 27. The eighth shaft was finally proven late in the contract and this was infilled within the extended contract period, with works completed by June 2021.

This unusual project was delivered very successfully, in part as a result of the close collaboration between Network Rail, COWI, Story Contracting and Geobear. It has proven the suitability of closed-cell geopolymers and further opportunities are foreseen.

ALL PHOTOS: PETER ALVEY