The Institution of Mechanical Engineers (IMechE) 10th Railway Challenge took place at the Stapleford Miniature Railway between 25-27 June 2021, with sponsorship from SNC-Lavalin Atkins, Angel Trains, Beacon Rail Leasing, Network Rail and RSSB.

The event provides a great opportunity for aspiring teams of young engineers to compete in a demanding industry-specific competition, showcasing their skills, expertise, knowledge and business acumen. Participants are required to design, manufacture and run a miniature (10¼” gauge) railway locomotive in accordance with strict rules and a detailed technical specification.

The locomotives are then tested over a single weekend at the Stapleford Miniature Railway in Leicestershire, where several category winners and an overall Railway Challenge champion are announced.

There are six track challenges: maintainability, auto-stop, ride, energy recovery, acceleration and noise, together with a derived reliability challenge. There are also three paper-based challenges: design, innovation and poster, as well as a business case challenge where teams have to pitch their design to a ‘Dragons’ Den’ of judges. In normal times, the business case challenge is held on the Saturday of the competition, but this year it was held virtually on 4 June.

Unlike 2020’s competition, which was held virtually, the easing of Covid restrictions allowed the track-based challenges to go ahead. It was a closed event and this report is based on the IMechE’s own news piece, together with input from colleagues.

Energy recovery

A total of 11 teams entered, but, because of restrictions imposed by the various lockdowns, only five had completed their locomotives and only four were allowed to travel to Stapleford. Ten teams participated in the non-track challenges which were virtual.

Teams from Alstom/University of Derby, the University of Huddersfield, Network Rail and the University of Sheffield arrived at Stapleford on 25 June and, during torrential rain showers, there was a great deal of ingenuity in simply providing reasonably waterproof joints between gazebos; pliers and cable ties were involved! These teams had also suffered disruption in constructing their locomotives.

Only the Huddersfield team was equipped to be able to attempt all the track challenges. Its locomotive was powered by a petrol generator feeding electric motors, with an energy recovery system built from clock springs and clutches mounted on one of the axles. Sadly, it failed to operate during the tests.

All the other teams used or, in the case of the teams not participating in the track challenges, proposed lead acid batteries feeding electric motors. Several different controllers and motor types were employed, providing teams with a variety of ‘interesting’ control system challenges. All but one of the locomotives were twin two-axle bogie vehicles, whilst Sheffield’s locomotive comprised two, two-axle vehicles. Apart from Huddersfield’s spring system, other teams used supercapacitors for energy recovery or simply fed the energy back into the main batteries.

Teams have always struggled with the energy recovery challenge. The rules state that the locomotive and its load must be braked to a halt and demonstrate to the judges that only the energy recovered in that brake application can be used to propel the train. This is not straightforward. How do you measure that energy?

The energy recovered in a single stop is not large and some teams simply measure the change in voltage of the supercapacitor. This can work providing an appropriately sized supercapacitor is used, something that was generally not an issue in the early days of the competition as the only affordable supercapacitors were quite small. Bigger devices have since become available, but teams have discovered that bigger is not necessarily better. Putting a small charge into a large supercapacitor results in a very small change of voltage – too small to convince a judge!

The same is true if the energy is fed back into the battery. Some teams have started to measure the energy in and out. This is better, but some account still needs to be taken of the losses in the charge/discharge cycle. The Aachen locomotive was one that used an energy meter approach. On the competition day, none of the locomotives successfully completed the energy recovery challenge and this award was not made.

Come to a stand

The other ‘challenging challenge’ is auto-stop. The train has to be moving at over 10kph and, on passing a set point, automatically apply its brakes to stop exactly 25m beyond the set point. Teams used or proposed a variety of trigger methods – optical sensor, infrared, magnet/reed switch, radar speed probe and Hall effect sensor. But none of the teams at Stapleford was able to deliver a successful auto-stop.

The team from FH Aachen University of Applied Sciences/Reuschling, 2019’s winners, was one of the five teams that had completed their locomotive, but they were unable to travel to the UK. As they had a small oval test track on a campus car park, the competition organisers arranged for a judge to witness a demonstration of their loco carrying out the majority of the track challenges on that test track and the maintainability challenge in their workshop.

The arrangement was that the loco would not be eligible for scoring on the track challenges as the geometry was so different from the Stapleford track. In addition, the ride and noise tests were not attempted. The judges were minded to make a special award for the German team’s ingenuity in setting up the remote demonstration, but, in the absence of any successful auto-stop challenge results at Stapleford, the judges decided to award them the auto-stop challenge certificate despite the limitations of their test track.

Together again

Two locomotives deserve special mention. Sheffield’s was clad in transparent panels so that its components were easy to see. The team uses its locomotive as part of its STEM outreach programme and one of the features is a series of coloured LED strips which provided almost disco-like illumination in the Stapleford tunnel. Network Rail’s loco arrived at Stapleford as a non-runner and it is a great tribute to its team that members were able to get it running and participate in the maintainability challenge. After prize giving on the Sunday, the team made a trip around the railway and there was a big cheer on departure.

It was obvious how much everyone valued the opportunity to do real things with other people, rather than participate in Teams or Zoom meetings. IMechE Education Programme Operations Manager, Jelena Gacesa, said that “The 2021 Railway Challenge honoured the work of students, apprentices and young professionals in the most challenging of circumstances. Together we celebrated their resilience, problem solving acumen and innovative solutions, reinforcing the importance of practical engineering skills in an increasingly virtual world.”

At the presentation ceremony, head judge Bill Reeve observed that “we are increasingly seeing past participants in quite senior roles within the railway industry. Time and time again, past competitors tell us that they look back on their Railway Challenge experience as the highlight of their training. For many, it allows them to gain competence towards their CEng that would otherwise be hard to get so early in their careers.”

For me, your writer, as a member of the Challenge’s Organising Committee and now a judge as well as a past team sponsor, this is one of the most rewarding things I’ve done in my 50+ year career.

The University of Huddersfield team were overall winners of the 2021 Railway Challenge, with the University of Sheffield taking the runners-up spot and the Alstom/University of Derby team third.

The winners of the individual challenges were:

- Auto-stop (automatically stop from >10kph in precisely 25m): FH Aachen/Reuschling

- Ride comfort (measured using a triaxial accelerometer over most of the railway’s loop section): University of Huddersfield

- Traction (accelerate in the shortest time over a 1:80 uphill section): University of Sheffield

- Noise (measured whilst accelerating in the traction challenge and corrected for speed): Alstom/University of Derby

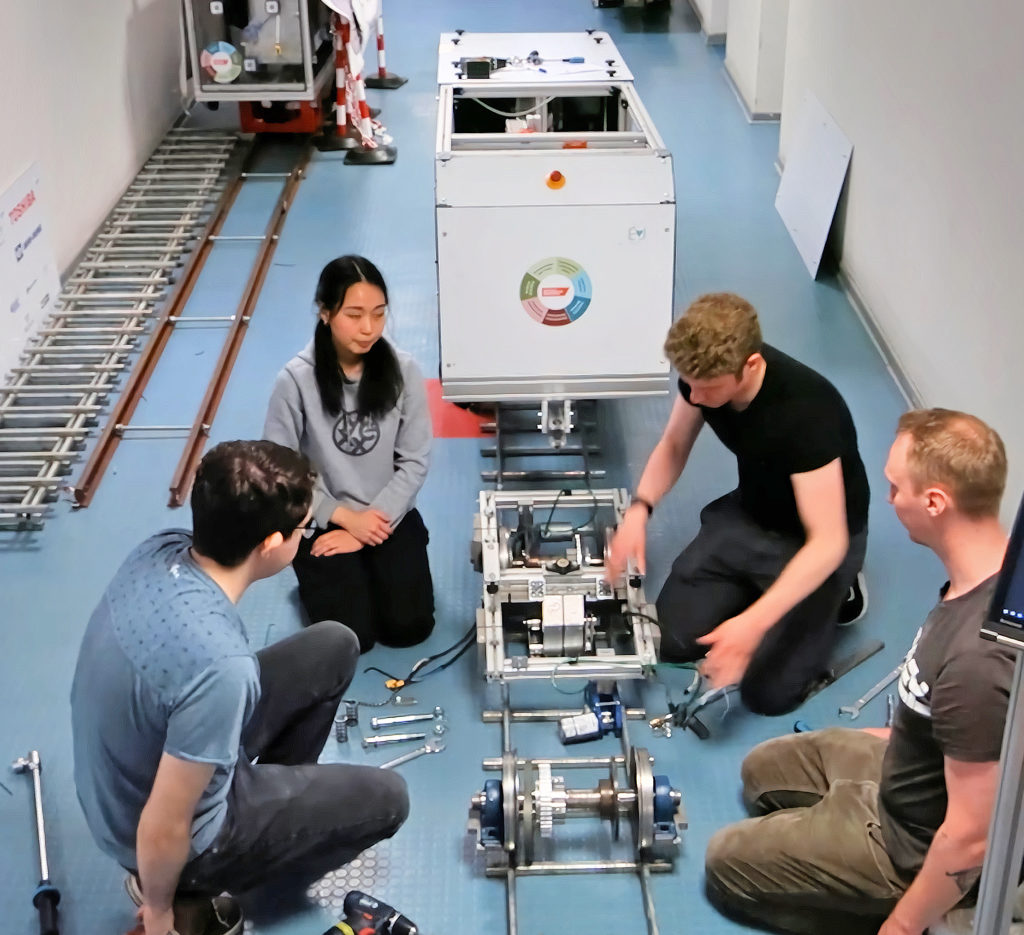

- Maintainability (safely remove and replace a wheelset in the quickest time): Alstom/University of Derby

- Business case (pitch the design to a ‘Dragon’s Den’ style panel): Newcastle University

- Technical poster (describe/illustrate the loco design for visitors to the competition): University of Birmingham

- Innovation (draft a technical paper about an innovation fitted to the locomotive): FH Aachen/Reuschling

- Design (draft a design review submission): Alstom/University of Derby

Rail Engineer adds its congratulations to all the teams who took part in the 2021 Railway Challenge. We are looking forward to covering the 2022 competition.